ICU Management & Practice, Volume 24 - Issue 2, 2024

The seamless integration of patient- and family-centred care in the critical care setting remains elusive. This review discusses the history and benefits of patient- and family-centred care, plus strategies for partnering with patients and families in the critical care setting.

Introduction

Patient and family partnerships in the intensive care unit (ICU) are an essential element of quality healthcare. Leading societies and organisations across the world have integrated families as key participants in shaping research priorities and improving hospital outcomes (Davidson et al. 2017; European Society of Intensive Care Medicine 2017; Feemster et al. 2018; Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute 2022). We define ‘family’ as a person or people identified by a patient as providing love, caregiving and/or support not necessarily related by blood or marriage. In this article, we 1) describe the history of patient- and family-centred care; 2) narrate the benefits of partnering with patients and families in the ICU; and 3) reflect on the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on partnerships with patients and families. We conclude with recommendations and resources to support current ICU providers in their efforts to incorporate patients and families into their daily ICU practice.

History of Patient- and Family-Centred Care

Patient- and family-centred care (PFCC) is a philosophy of care that is “grounded in mutually beneficial partnerships among healthcare providers, patients, and families” and supports patients and families in “determining how they will participate in care and decision-making”. It recognises patients and families as essential allies—not only in direct care and decision-making but also in quality improvement, safety initiatives, education of health professionals, research, facility design, and policy development (Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care).

The family-centred care movement emerged as a major response to the widespread separation of children from their families during World War II (Isaacs 2019; Jolley and Shields 2009). Through the mid-20th century, it was common for children to be hospitalised for extended periods (Robertson 1970). Efforts to control disease spread led to restricting family visits to once a week, causing lasting psychological trauma to children (Robertson 1970). Until the 1960s, families were often kept out of the paediatric hospital care process. British researchers John Bowlby and James Robertson played pivotal roles in studying family separation during hospitalisation and advocating for the inclusion of parents in the care of hospitalised children (Alsop-Shields and Mohay 2001).

The evolution of U.S. healthcare to focus on patient-centred outcomes owes much to Avedis Donabedian's influential work. In his landmark 1966 paper, “Evaluating the Quality of Medical Care”, Donabedian advocated for evaluating healthcare quality not only in disease management but also in care processes and patient-physician relationships (Donabedian 1966). His 1990 publication, "Seven Pillars of Quality", identified key aspects of healthcare quality: efficacy, effectiveness, efficiency, optimality, acceptability, legitimacy, and equity (Donabedian 1990). He explicated the importance of care acceptability as including the patient-practitioner relationship, accessibility, amenities, and patient preferences regarding care effects and costs. The importance of patient and family engagement was echoed in the Institute of Medicine’s 2001 report "Crossing the Quality Chasm", which outlined aims for 21st-century healthcare: safety, effectiveness, patient-centredness, timeliness, efficiency, and equity (Baker 2001). These factors helped shape PFCC, and from this, PFCC in ICUs took shape.

In 2004, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement called for open ICU visitation policies (Berwick and Kotagal 2004). Despite the acknowledged importance of family presence and partnership in the ICU, barriers to family engagement remain. For example, a study of family engagement in the ICU found while 97% of family members were willing to participate in patient care, only 13.8% spontaneously participated or asked the ICU staff to help them participate (Garrouste-Orgeas et al. 2010). The emphasis on quality has led to the development of quality assessment measures like the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS), the Family Satisfaction in the ICU (FS-ICU), and the Critical Care Family Needs Inventory (CCFNI) (Giordano et al. 2010; Molter 1979; Wall et al. 2007). More recent data shows families consider addressing patient psychosocial and spiritual needs as one of the most important ways they can participate in the ICU (Wong et al. 2019; Wong et al. 2020).

Benefits of Partnering With Patients and Families in the ICU

PFCC has gained prominence in critical care medicine and research in recent decades. For instance, a 2000 survey of U.K. clinicians ranked the impact of visitors on patient outcomes as one of the lowest priorities for ICU research (Goldfrad et al. 2000). However, by 2007, guidelines for PFCC in the ICU were introduced by the American College of Critical Care Medicine and updated in 2017 (Davidson et al. 2017; Davidson et al. 2007). These guidelines, along with the ABCDEF bundle—which integrates family involvement and improves patient survival and post-discharge disposition—underscore the importance of family engagement in care (Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care 2014; Marra et al. 2017; Pun et al. 2019). In a 2023 systematic review of randomised trials with family-centred interventions, 35 of 52 studies showed improvement in at least one family-centred outcome (Wang et al. 2023). (Tellingly, only 5 of the included studies occurred before 2010).

There is broad evidence for the benefit of using family caregivers to implement evidence-based interventions in the inpatient setting and a small but growing evidence base for their participation in direct ICU care (Dijkstra et al. 2023b; Fiest et al. 2018). Families want to participate in patient care, and ICU teams are generally supportive (Al-Mutair et al. 2013; Dijkstra et al. 2023a; Liput et al. 2016). Engaging family caregivers can improve hospital quality metrics vis-a-vis satisfaction ratings and implementation of best practices for reducing hospital-acquired weakness and delirium (Davidson et al. 2017; Fiest et al. 2018; Guerra-Martin and Gonzalez-Fernandez 2021; Rosgen et al. 2018; Rukstele and Gagnon 2013). Similarly, engaging caregivers in patient mobilisation in the hospital improves long-term patient mobility and home caregiver quality of life and reduces patient length of stay (Yasmeen et al. 2020). While clinicians and families see value in forming partnerships, the seamless integration of PFCC into ICU practice remains elusive.

A 2017 systematic review of ICU PFCC interventions demonstrated that PFCC interventions were associated with reduced ICU costs, shortened ICU length of stay, improved family satisfaction, and improved patient and family mental health outcomes (Goldfarb et al. 2017). For example, multicomponent trials of ICU patients with high risk of death by White and Curtis used nurse communication facilitators to support families; both studies showed reduced ICU length of stay (Curtis et al. 2016; White et al. 2018). In general, there is no single “silver bullet” intervention that addresses all patient and family needs for partnership in the ICU; it is, therefore, recommended that interventions have multiple components and engage patients and families as partners in multiple aspects (Xyrichis et al. 2021).

The ICU experience can provoke significant emotional stress for patients and families (Gurbuz and Demir 2023; Kose et al. 2016; Pochard et al. 2001). Individual clinician, ICU culture, and geographic area differences all contribute to a lack of standard approach for discussions about value-based treatment plans and patient preference alignment (Turnbull et al. 2016). Surrogate decision-making around potentially medically non-beneficial treatments or end-of-life treatment thresholds burdens families and patients with guilt and confusion and is associated with poor psychological outcomes (Greenleaf et al. 2023; Wen et al. 2024). Symptoms of Post-Intensive Care Syndrome-Family (PICS-F), a constellation of psychological symptoms including anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress, and complicated grief, can affect up to 73% of family caregivers (Davidson et al. 2012; Kentish-Barnes et al. 2015; Lautrette et al. 2007; Pochard et al. 2001; Pochard et al. 2005). Furthermore, patient and family employment absenteeism and hospital financial expenses accrue additional psychological strain and suffering (Khandelwal et al. 2020; Khandelwal et al. 2018; Stayt and Venes 2019). The intersection of these and other complex variables can result in depression, post-traumatic stress, anxiety, and care that is often inconsistent with the patient’s previously expressed preferences (Vrettou et al. 2022). Embracing PFCC in the ICU is one way clinicians can help to mitigate emotional stress and PICS-F (Love Rhoads et al. 2022).

The emotional burden families carry can be exacerbated by communication breakdowns between physicians and surrogate decision-makers of critically ill patients (Connors et al. 1995; Ito et al. 2023). Provider disruption in the continuity of care, insufficient clinician training around palliative care, and difficult conversations are just a few of the barriers to successful communication with patients and families in the ICU and highlight the lack of consistent patient- and family-centred systems (Connors et al. 1995; Pochard et al. 2001; Schwartz et al. 2022). Recognising the essential role PFCC has in the care of critically ill patients is paramount to ensuring the successful transition of recovered critically ill patients and their families to healthy lives. Interventions to improve surrogate decision-making may reduce ICU length of stay without changing the mortality rate (Bibas et al. 2019). Overall, taking a proactive, structured approach to foster open communication, provide surrogate support, and engage families in treatment and medical decision-making is essential for PFCC (Azoulay and Sprung 2004; Lautrette et al. 2007; Schwartz et al. 2022).

Learnings from COVID-19: Family Partnerships and Presence in the ICU

The Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care (IPFCC) is a non-profit organisation based in the United State providing leadership in understanding and advancing the practice of PFCC in all care settings. As part of its mission, IPFCC champions family presence and participation through its Better Together campaign (Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care 2014). The campaign embraces families as essential members of the healthcare team and reduces restrictions on their presence and participation (Dokken et al. 2020; Dokken et al. 2015).

In Spring 2020, faced with the tremendous uncertainty of the COVID-19 pandemic, severe restrictions on family presence were imposed by health systems globally. The sudden and widespread implementation of these restrictions led to serious consequences and harm to ICU patients, their families, clinicians, and staff. For example, a study of ICUs in 49 Michigan hospitals documented high rates of delirium and sedation requirements in patients with COVID-19, two conditions that are reduced by increased access to family members (Valley et al. 2020). Unable to visit loved ones in the hospital, family members had increased psychological distress (Heesakkers et al. 2022).

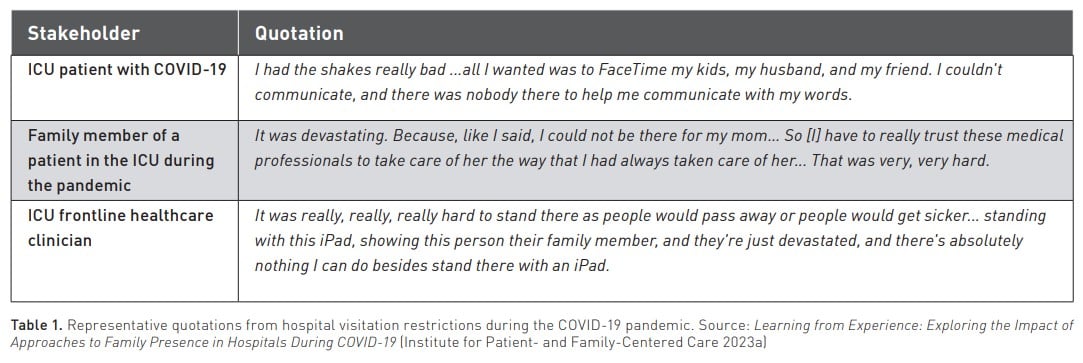

To better understand the impact of visitor restrictions, IPFCC partnered with health systems in an engagement project, “Learning from Experience: Exploring the Impact of Approaches to Family Presence in Hospitals During COVID-19” (Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care 2023a). The project’s purpose was to learn directly from patients, families, and healthcare workers about the impact of the restrictive family presence policies during the pandemic. Not surprisingly, the restrictive policies negatively impacted patient care, communication, information sharing, decision making and the emotional well-being of clinicians, families, and patients. Derived from participants who experienced hospital settings during COVID-19, these themes reinforce the benefits of family partnership (Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care 2023a). The IPFCC project was able to capture quotes from participants that illustrate the helplessness felt by patients, families, and clinicians when families are not allowed to be present and participate in the care of their loved ones (Table 1).

Despite growing evidence about the negative consequences of restricting family presence, many hospitals have not returned to pre-pandemic levels of open visitation and welcoming family members as partners and allies (Fernández-Castillo et al. 2024; Marmo and Hirsch 2023; McTernan 2023). Emerging and anecdotal evidence suggests this is a global phenomenon (Fernández-Castillo et al. 2024).

Strategies for Increasing Patient and Family Partnership

Involving Families in Care

Family members know the patient, their health history, and how care is managed at home—their deep understanding of their loved one provides a humanistic context for the patient’s care in the ICU.Clinicians should be prepared to use a consistent and standardised approach in partnering with patients and families. Useful guides for families about how they can be involved in care and decision-making are available online (European Society of Intensive Care Medicine 2017; Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care 2014; Minniti and Abraham 2013).

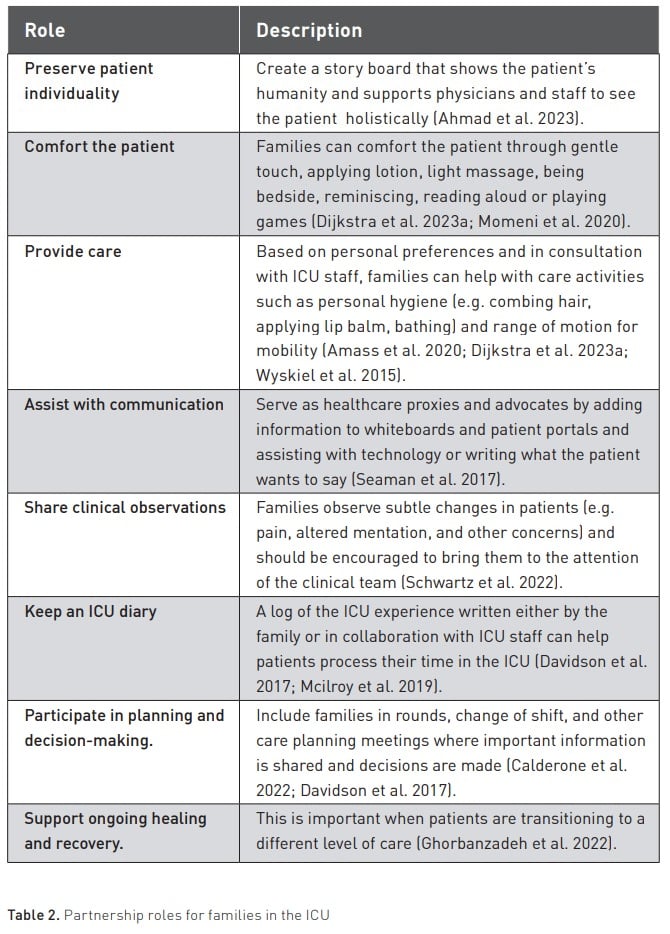

Involving families in care requires commitment from both families and healthcare professionals. To effectively integrate families as care partners, it is critical to provide families with clear expectations of their roles. These include: 1) maintaining the patient’s identity, i.e., enabling clinicians to understand the patient within their life’s context; 2) assisting with communication between the patient and healthcare team, including shared medical decision-making; and 3) acting as advocates for the patient (Ahmad et al. 2023; Calderone et al. 2022). Families can collaborate with staff to keep a diary to help patients process their time in the ICU. These diaries are associated with improved patient quality of life, decrease depression and anxiety, and may also reduce family caregiver post-traumatic distress (Mcilroy et al. 2019). A more detailed list of family roles can be found in Table 2.

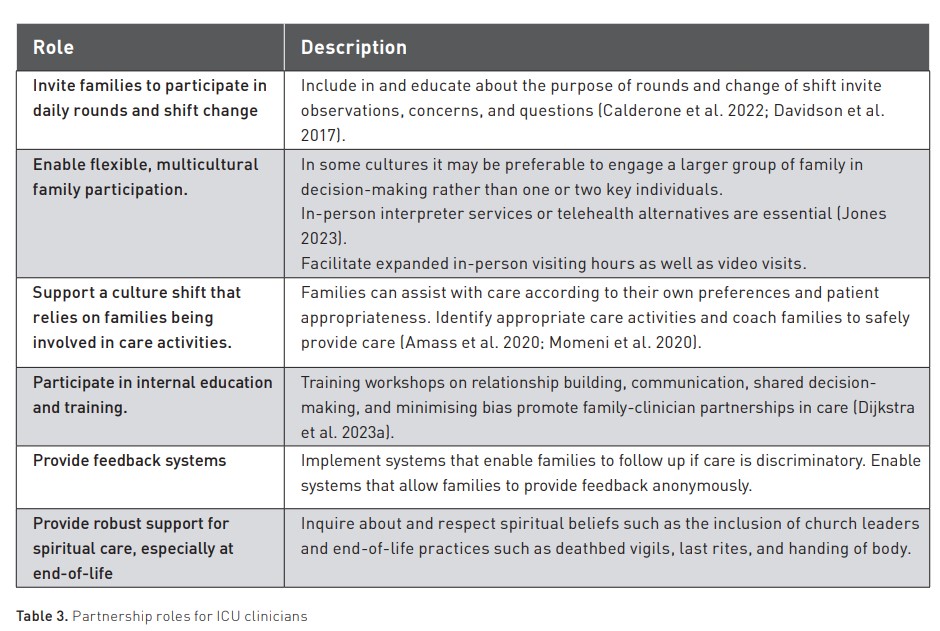

Clinicians and healthcare staff can: 1) offer options for communication, including personalised technology and translation services; 2) encourage patients and families to participate in rounds and change of shift, and educate them about the ICU environment, the purpose of rounds and shift change sign out; and 3) encourage families to ask questions, provide observations and assist with care activities according to the family’s preferences (Calderone et al. 2022). Ultimately, ICU clinicians should strive to engage families in caring for patients and shared medical decision-making (Table 3) (Dijkstra et al. 2023a). A useful guide for clinicians and staff is available online (Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care 2014).

Involving Patients and Families in Improvement and Change

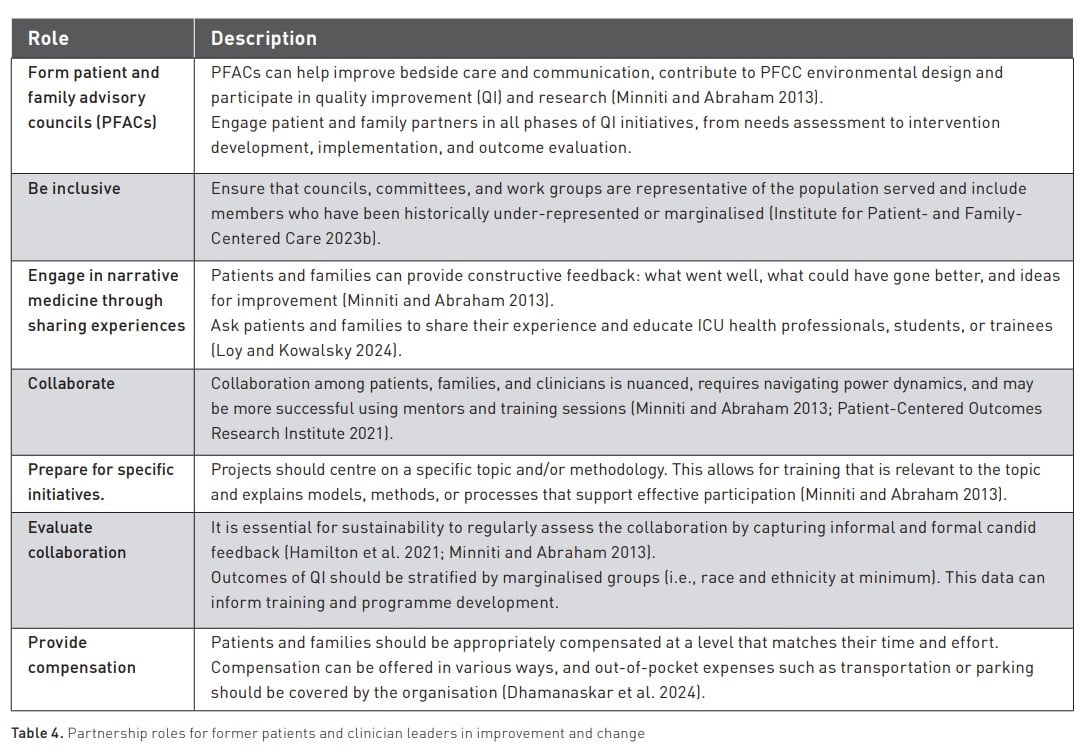

Former ICU patients and family caregivers have insight into the needs, values, and experiences of patients and families. Close partnerships—through collaborative committees, patient and family advisory councils, formal evaluations, and feedback systems—ensure patient and family voices are represented in organisational change (Schwartz et al. 2022). Partnership with patients and families is facilitated by identifying barriers, exploiting facilitators, and achieving buy-in at each level of engagement (Kiwanuka et al. 2019). An important consideration is ensuring that patients and family partners represent diverse perspectives and backgrounds, including diversity of race, ethnicity, religion, gender, education, socioeconomics, and disability status. Information about engaging former patients and families in change can be found in the resource, Essential Allies: Patient, Resident, and Family Advisors (Minniti and Abraham 2013). Additional strategies for improvement and change can be found in Table 4.

Conclusion

We discussed the importance of PFCC and patient and family partnership in the ICU for achieving high-quality healthcare. Organisational leaders, clinicians, and community members recognise the value of these partnerships for inpatient and outpatient care and the improvement of health systems. Buy-in and conscious integration of family partnerships in the ICU are required from clinicians, policymakers, and other non-clinical staff to achieve the desired cultural shift. The tables offer resources and recommendations that we hope will serve as a starting point to help interested parties implement PFCC worldwide.

Conflict of Interest

JH Neiman’s Health Services Research Fellowship is funded by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations (TPH-21-000) and the Durham Center of Innovation to Accelerate Discovery and Practice Transformation (CIN-13-410). The other authors have no conflicts to report.

References:

Ahmad SR, Rhudy L, Fogelson LA et al. (2023) Humanizing the Intensive Care Unit: Perspectives of Patients and Families on the Get to Know Me Board. J Patient Exp. 10.

Al-Mutair AS, Plummer V, O'Brien A et al. (2013) Family needs and involvement in the intensive care unit: a literature review. J Clin Nurs. 22(13-14):1805-17.

Alsop-Shields L, Mohay H (2001) John Bowlby and James Robertson: theorists, scientists and crusaders for improvements in the care of children in hospital. J Adv Nurs. 35(1):50-8.

Amass TH, Villa G, O’Mahony S et al. (2020) Family Care Rituals in the ICU to Reduce Symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Family Members-A Multicenter, Multinational, Before-and-After Intervention Trial. Crit Care Med. 48(2):176-84.

Azoulay E, Sprung CL (2004) Family-physician interactions in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 32(11):2323-8.

Baker A (2001) Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. BMJ. 323(7322).

Berwick DM, Kotagal M (2004) Restricted visiting hours in ICUs: time to change. JAMA. 292(6):736-7.

Bibas L, Peretz-Larochelle M, Adhikari NK et al. (2019) Association of Surrogate Decision-making Interventions for Critically Ill Adults With Patient, Family, and Resource Use Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2(7):e197229.

Calderone A, Debay V, Goldfarb MJ (2022) Family Presence on Rounds in Adult Critical Care: A Scoping Review. Crit Care Explor. 4(11):e0787.

Connors AF, Dawson NV, Desbiens NA et al. (1995) A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients: The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). JAMA. 274(20):1591-98.

Curtis JR, Treece PD, Nielsen EL et al. (2016) Randomized Trial of Communication Facilitators to Reduce Family Distress and Intensity of End-of-Life Care. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 193(2):154-62.

Davidson JE, Aslakson RA, Long AC et al. (2017) Guidelines for Family-Centered Care in the Neonatal, Pediatric, and Adult ICU. Crit Care Med. 45(1):103-28.

Davidson JE, Jones C, Bienvenu OJ (2012) Family response to critical illness: postintensive care syndrome-family. Crit Care Med. 40(2):618-24.

Davidson JE, Powers K, Hedayat KM et al. (2007) Clinical practice guidelines for support of the family in the patient-centered intensive care unit: American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004-2005. Crit Care Med. 35(2):605-22.

Dhamanaskar R, Tripp L, Vanstone M et al. (2024) Patient partner perspectives on compensation: Insights from the Canadian Patient Partner Survey. Health Expectations. 27(1): e13971.

Dijkstra B, Uit Het Broek L, van der Hoeven J et al. (2023a) Feasibility of a standardized family participation programme in the intensive care unit: A pilot survey study. Nurs Open 10(6):3596-602.

Dijkstra BM, Felten-Barentsz KM, van der Valk MJM et al. (2023b) Family participation in essential care activities in adult intensive care units: An integrative review of interventions and outcomes. J Clin Nurs. 32(17-18):5904-22.

Dokken D, Barden A, Tuomey M et al. (2020) Families as Care Partners: Implementing the Better Together Initiative Across a Large Health System. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 27(1).

Dokken D, Kaufman J, Johnson B et al. (2015) Changing hospital visiting policies: From families as "visitors" to families as partners. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 22(1):29-36.

Donabedian A (1966) Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 44(3): Suppl:166-206.

Donabedian A (1990) The seven pillars of quality. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 114(11):1115-8.

European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (2017) Patient and Family 2017. Available at https://www.esicm.org/patient-and-family/

Feemster LC, Saft HL, Bartlett SJ et al. (2018) Patient-centered Outcomes Research in Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine. An Official American Thoracic Society Workshop Report. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 15(9):1005-15.

Fernández-Castillo RJ, González-Caro MD, Arroyo-Muñoz FJ et al. (2024) Encuesta nacional sobre cambios en las políticas de comunicación, visitas y cuidados al final de la vida en las unidades de cuidados intensivos durante las diferentes olas de la pandemia de COVID-19 (estudio COVIFAUCI). Enfermería Intensiva. 35(1):35-44.

Fiest KM, McIntosh CJ, Demiantschuk D et al. (2018) Translating evidence to patient care through caregivers: a systematic review of caregiver-mediated interventions. BMC medicine. 16(1):105.

Garrouste-Orgeas M, Willems V, Timsit J-F et al. (2010) Opinions of families, staff, and patients about family participation in care in intensive care units. Journal of critical care. 25(4):634-40.

Ghorbanzadeh K, Ebadi A, Hosseini M et al. (2022) Transition of patients from intensive care unit: A concept analysis. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences. 17:100498.

Giordano LA, Elliott MN, Goldstein E et al. (2010) Development, implementation, and public reporting of the HCAHPS survey. Med Care Res Rev. 67(1):27-37.

Goldfarb MJ, Bibas L, Bartlett V et al. (2017) Outcomes of Patient- and Family-Centered Care Interventions in the ICU: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit Care Med. 45(10):1751-61.

Goldfrad C, Vella K, Bion JF et al. (2000) Research priorities in critical care medicine in the UK. Intensive Care Med. 26(10):1480-8.

Greenleaf B, Foy A, Van Scoy L (2023) Relationships Between Personality Traits and Perceived Stress in Surrogate Decision-Makers of Intensive Care Unit Patients. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine.

Guerra-Martin MD, Gonzalez-Fernandez P (2021) Satisfaction of patients and family caregivers in adult intensive care units: Literature Review. Enferm Intensiva (Engl Ed). 32(4):207-19.

Gurbuz H, Demir N (2023) Anxiety and Depression Symptoms of Family Members of Intensive Care Unit Patients: A Prospective Observational Study and the Lived Experiences of the Family Members. Avicenna J Med. 13(2):89-96.

Hamilton CB, Dehnadi M, Snow ME et al. (2021) Themes for evaluating the quality of initiatives to engage patients and family caregivers in decision-making in healthcare systems: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 11(10):e050208.

Heesakkers H, van der Hoeven JG, Corsten S et al. (2022) Mental health symptoms in family members of COVID-19 ICU survivors 3 and 12 months after ICU admission: a multicentre prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 48(3):322-31.

Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care (n.d.) What is PFCC? Available at https://www.ipfcc.org/about/pfcc.html

Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care (2014) Better Together: Partnering with Families.

Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care (2023a) Learning from experience: Exploring the impact of approaches to family presence in hospitals during COVID-19. Themes, topics, questions, recommendations.

Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care (2023b) Strengthening the diversity and role of patient and family advisory councils: Opportunities for action Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care.

Isaacs S (2019) The Cambridge evacuation survey: A wartime study in social welfare and education.

Ito Y, Tsubaki M, Kobayashi M et al. (2023) Effect size estimates of risk factors for post-intensive care syndrome-family: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Lung. 59:1-7.

Jolley J, Shields L (2009) The evolution of family-centered care. J Pediatr Nurs. 24(2):164-70.

Jones M (2023) Improving family communication in critical care. Canadian Journal of Critical Care Nursing. 34(1).

Kentish-Barnes N, Chaize M, Seegers V et al. (2015) Complicated grief after death of a relative in the intensive care unit. Eur Respir J. 45(5):1341-52.

Khandelwal N, Engelberg RA, Hough CL et al. (2020) The Patient and Family Member Experience of Financial Stress Related to Critical Illness. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 23(7): 972-76.

Khandelwal N, Hough CL, Downey L et al. (2018) Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Outcomes of Financial Stress in Survivors of Critical Illness. Critical Care Medicine. 46(6):E530-E39.

Kiwanuka F, Shayan SJ, Tolulope AA (2019) Barriers to patient and family-centred care in adult intensive care units: A systematic review. Nurs Open. 6(3):676-84.

Kose I, Zincircioglu C, Ozturk YK et al. (2016) Factors Affecting Anxiety and Depression Symptoms in Relatives of Intensive Care Unit Patients. J Intensive Care Med. 31(9):611-7.

Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B et al. (2007) A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 356(5):469-78.

Liput SA, Kane-Gill SL, Seybert AL et al. (2016) A Review of the Perceptions of Healthcare Providers and Family Members Toward Family Involvement in Active Adult Patient Care in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 44(6):1191-7.

Love Rhoads S, Trikalinos TA, Levy MM et al. (2022) Intensive Care Based Interventions to Reduce Family Member Stress Disorders: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J Crit Care Med (Targu Mures). 8(3):145-55.

Loy M, Kowalsky R (2024) Narrative Medicine: The Power of Shared Stories to Enhance Inclusive Clinical Care, Clinician Well-Being, and Medical Education. Perm J. 1-9.

Marmo S, Hirsch J (2023) Visitors not Welcome: Hospital Visitation Restrictions and Institutional Betrayal. Journal of Policy Practice and Research. 4(1):28-40.

Marra A, Ely EW, Pandharipande PP et al. (2017) The ABCDEF Bundle in Critical Care. Crit Care Clin. 33(2):225-43.

McIlroy PA, King RS, Garrouste-Orgeas M et al. (2019) The Effect of ICU Diaries on Psychological Outcomes and Quality of Life of Survivors of Critical Illness and Their Relatives: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit Care Med. 47(2):273-79.

McTernan E (2023) Against visitor bans: freedom of association, COVID-19 and the hospital ward. J Med Ethics. 49(4):288-91.

Minniti MM, Abraham MR (2013) Essential Allies; Patient, Resident and Family Advisors: A Guide for Staff Liaisons Institute for Patient-and Family-Centered Care.

Molter NC (1979) Needs of relatives of critically ill patients: a descriptive study. Heart Lung. 8(2):332-9.

Momeni M, Arab M, Dehghan M et al. (2020) The Effect of Foot Massage on Pain of the Intensive Care Patients: A Parallel Randomized Single-Blind Controlled Trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 3450853.

Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (2021) Building effective multi-stakeholder research teams. Available at https://research-teams.pcori.org/

Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (2022) Strategic Plan.Washington, DC.

Pochard F, Azoulay E, Chevret S et al. (2001) Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients: ethical hypothesis regarding decision-making capacity. Critical care medicine. 29(10):1893-97.

Pochard F, Darmon M, Fassier T et al. (2005) Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients before discharge or death. A prospective multicenter study. J Crit Care. 20(1):90-6.

Pun BT, Balas MC, Barnes-Daly MA et al. (2019) Caring for Critically Ill Patients with the ABCDEF Bundle: Results of the ICU Liberation Collaborative in Over 15,000 Adults. Crit Care Med. 47(1):3-14.

Robertson J (1970) Young Children in Hospital 2nd edition. UK: Tavistock Publications.

Rosgen B, Krewulak K, Demiantschuk D et al. (2018) Validation of Caregiver-Centered Delirium Detection Tools: A Systematic Review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 66(6):1218-25.

Rukstele CD, Gagnon MM (2013) Making strides in preventing ICU-acquired weakness: involving family in early progressive mobility. Crit Care Nurs Q. 36(1):141-7.

Schwartz AC, Dunn SE, Simon HFM et al. (2022) Making Family-Centered Care for Adults in the ICU a Reality. Front Psychiatry. 13:837708.

Seaman JB, Arnold RM, Scheunemann LP et al. (2017) An Integrated Framework for Effective and Efficient Communication with Families in the Adult Intensive Care Unit. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 14(6):1015-20.

Stayt LC, Venes TJ (2019) Outcomes and experiences of relatives of patients discharged home after critical illness: a systematic integrative review. Nursing in Critical Care. 24(3):162-75.

Turnbull AE, Davis WE, Needham DM et al. (2016) Intensivist-reported Facilitators and Barriers to Discussing Post-Discharge Outcomes with Intensive Care Unit Surrogates. A Qualitative Study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 13(9):1546-52.

Valley TS, Schutz A, Nagle MT et al. (2020) Changes to Visitation Policies and Communication Practices in Michigan ICUs during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 202(6):883-85.

Vrettou CS, Mantziou V, Vassiliou AG et al. (2022) Post-Intensive Care Syndrome in Survivors from Critical Illness including COVID-19 Patients: A Narrative Review. Life. 12(1):107.

Wall RJ, Engelberg RA, Downey L et al. (2007) Refinement, scoring, and validation of the Family Satisfaction in the Intensive Care Unit (FS-ICU) survey. Crit Care Med. 35(1):271-9.

Wang G, Antel R, Goldfarb M (2023) The Impact of Randomized Family-Centered Interventions on Family-Centered Outcomes in the Adult Intensive Care Unit: A Systematic Review. J Intensive Care Med. 38(8):690-701.

Wen FH, Prigerson HG, Hu TH et al. (2024) Associations Between Family-Assessed Quality-of-Dying-and-Death Latent Classes and Bereavement Outcomes for Family Surrogates of ICU Decedents. Crit Care Med.

White DB, Angus DC, Shields AM et al. (2018) A Randomized Trial of a Family-Support Intervention in Intensive Care Units. N Engl J Med. 378(25):2365-75.

Wong P, Liamputtong P, Koch S et al. (2019) Searching for meaning: A grounded theory of family resilience in adult ICU. J Clin Nurs. 28(5-6):781-91.

Wong P, Redley B, Digby R et al. (2020) Families' perspectives of participation in patient care in an adult intensive care unit: A qualitative study. Aust Crit Care. 33(4):317-25.

Wyskiel RM, Weeks K, Marsteller JA (2015) Inviting Families to Participate in Care: A Family Involvement Menu. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 41(1):43-46.

Xyrichis A, Fletcher S, Philippou J et al. (2021) Interventions to promote family member involvement in adult critical care settings: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 11(4):e042556.

Yasmeen I, Krewulak KD, Grant C et al. (2020) The Effect of Caregiver-Mediated Mobility Interventions in Hospitalized Patients on Patient, Caregiver, and Health System Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Arch Rehabil Res Clin Transl. 2(3):100053.