ICU Management & Practice, Volume 23 - Issue 5, 2023

This article aims to address patient-family-centred care programmes, starting from their origins and discussing new protocols.

Critically ill patients entail a great complexity of care. ICU staff has focused on their care, with family members and surrogates put aside for decades. In recent years, we are witnessing a paradigm shift led by nursing teams (Clark and Guzzetta 2017; Davidson 2009) and professionals dedicated to the paediatric patient (Griffin 2006; Lee et al. 2014; Wratney 2019): patient and family-centred care (PFCC) is here to stay.

The Dawning of PFCC

In 1993, the Picker Institute introduced the concept of "patient-centred care" as a response to growing concerns about disease-centred or clinician-centred care. Attempts to change this disease-focused care (and paternalistic model) earmarked six dimensions of healthcare improvement: (1) respect for patient's values, preferences, and expressed needs; (2) coordination and integration of care; (3) information, communication, and education; (4) physical comfort; (5) emotional support; and (6) involvement of family and friends (Gerteis et al. 1993; Todres et al. 2009; Tzelepis et al. 2014). A respectful ICU requires recognition of fundamental human needs (physical, emotional, and psychological safety), acknowledgement of patients as unique individuals, and attention to the critical status and vulnerability of patients and families in the ICU (Azoulay and Sprung 2004; Bidabadi et al. 2019; Brown et al. 2018; Gazarian et al. 2021).

Critical illness of a loved one has enormous effects on family members, with approximately one-quarter to one-half of family members experiencing significant psychological symptoms, including acute stress, generalised anxiety, and depression both during and after the critical illness (impact termed as post-intensive care syndrome family; PICS-F) (Davidson et al. 2012; Lautrette et al. 2007; Needham et al. 2012). Families become essential caregivers, and we must support them: we must help mitigate the impact of the crisis of critical illness, prepare them for decision-making and caregiving demands, facilitate ethical shared decision-making, and promote their engagement during the ICU stay. High-quality family-centred care should be considered a fundamental skill for ICU clinicians (Gerritsen et al. 2017; Kang 2023). Increasing awareness of the vital role of family members in the ICU (and their continuous support) has shown improved outcomes for the family caregivers and patient outcomes (Adelman et al. 2014; Alonso-Ovies and Heras la Calle 2020; Lynn 2014). This trend has led to the "ICU humanisation movement" (de la Fuente-Martos et al. 2018; Nin Vaeza et al. 2020).

Starting Point: Guidelines 2007 and 2017

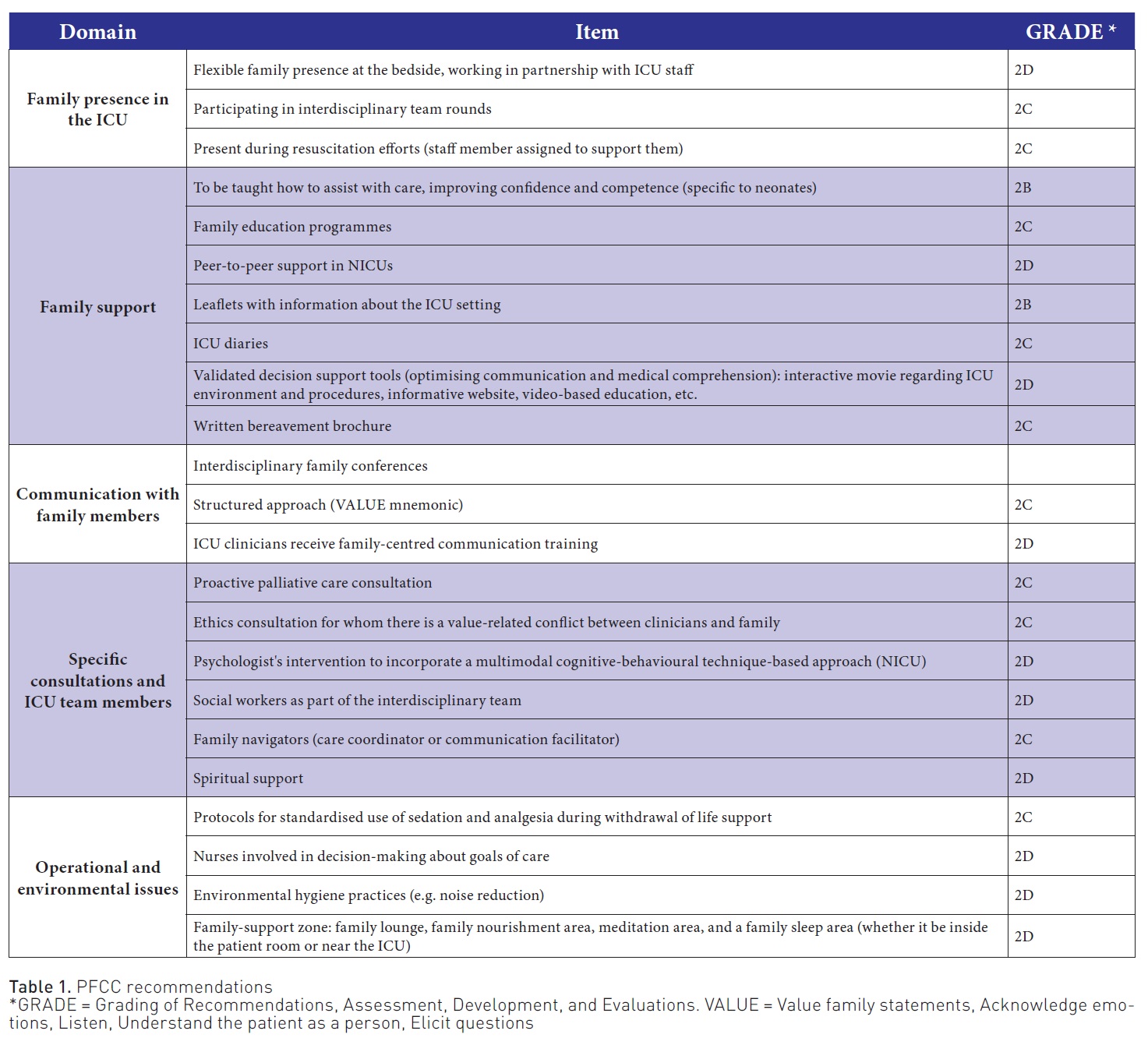

In 2007, the "Clinical practice guidelines for support of the family in the patient-centred intensive care unit" were published (Davidson et al. 2007). By 2017, the same group performed a new and more rigorous analysis, publishing new guidelines representing the current state of international science in family-centred care and family support for family members of critically ill patients across the lifespan (Davidson et al. 2017).

Within the guidelines, patient- and family-centred care is a model of providing care in which the patient and family ally with the care team. Table 1 summarises the most relevant points.

A little later, (Goldfarb et al. 2017) published a systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the outcomes of PFCC interventions. They found that over three-quarters of PFCC interventions were associated with improvements in at least one outcome measure (increased patient and family satisfaction, improved mental health status, and decreased resource use, including decreased ICU length-of-stay (LOS)). In contrast, by 2022 (Bohart et al. 2022) concluded that it was uncertain if PFCC, compared to usual care, reduced post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), delirium days, anxiety, and depression in patients due to limited and low certainty evidence. There is, therefore, a need for randomised controlled trials (RCT) on the effect of multi-component PFCC interventions on core outcomes for longer-term recovery in patients and families after ICU admission.

Barriers to Achieving PFCC

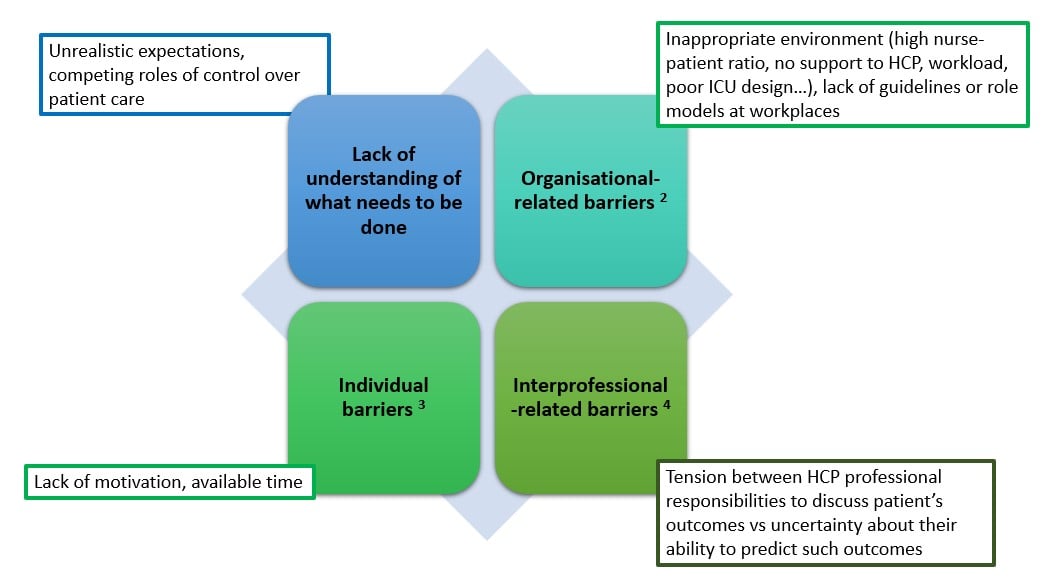

According to Kiwanuka et al. (2019), barriers to achieving PFCC across studies could be classified into four categories (Figure 1). For patient‐centred care to become truly embedded in the healthcare system, it must depend on reliable systems rather than individuals. Organisational and teamwork factors profoundly impact quality and care outcomes, particularly in the ICU, where administrative and teamwork factors are central to daily operations (Long et al. 2016; Ludmir and Netzer 2019).

Figure 1. Barriers to achieving PFCC

What is Brewing Within the ICU Programmes?

Input from the Paediatric ICU (PICU)

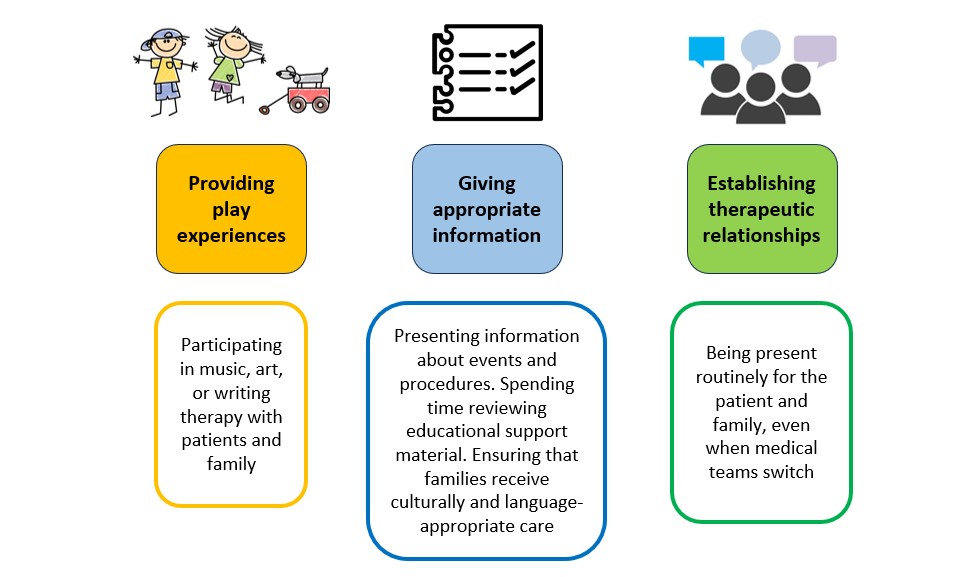

Addressing children's social and emotional needs during hospitalisation was initially acknowledged in the 1920s and 1930s and formalised in the 1950s. Child life providers focus on helping both the child and family cope with illness through the following: (a) providing play experiences, (b) presenting developmentally appropriate information about events and procedures, and (c) establishing therapeutic relationships with children and parents to support family involvement in each child's care (Bruce and McCue 2018). Based on child life providers, adult life providers may provide family support based on an adaptation of the following three core child life principles (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Adult life providers

Other developments coming from the PICU are the use of virtual family-centred rounds (Rosenthal et al. 2021), involving the family in the daily care of the patient (Verma et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2018) and focusing efforts on family members with long-stay ICU patients (Erçin-Swearinger et al. 2022).

Strengthening communication

Many articles regarding PFCC stress the importance of information and communication. The lack of fluid communication between the two sides of the clinical relationship forces families to seek answers from unreliable sources. Without adequate communication, decision-making, so necessary for the critically ill patient, may be based on misunderstood or incomplete information. It is, therefore, indispensable to improve communication skills through training, identify possible barriers, create a calm environment that favours communication and dedicate the necessary time so that they can raise any doubts they may have (Azoulay and Sprung 2004).

As conceptualised by Seaman et al. (2017), effective communication requires multiple communication platforms. Optimal communication is enabled when family-centred rounds, daily updates, patient portals, and interdisciplinary family meetings are combined (Scheunemann et al. 2011; Valls-Matarín and Del Cotillo-Fuente 2022). This allows their strengths to complement and their weaknesses to offset each other. In a recent trial of a comprehensive family support intervention in the ICU, surrogate decision-makers in the intervention group reported a higher quality of communication and a degree of patient-centredness and family-centredness. However, there was no difference in surrogates' symptoms of anxiety or depression six months after ICU discharge (White et al. 2018). Additionally, protocolised family support interventions demonstrated improved communication, enhanced shared decision-making with family, and reduced ICU length of stay (Lee et al. 2019).

Lastly, we must not forget that all communication must occur in an environment of respect and empathy. ICU-CORE (Beach et al. 2018) and EDMCQ (Ethical Decision- Making Climate Questionnaire) (Van den Bulcke et al. 2018) are self-assessment instruments used to measure the overall environment and climate of respect in the ICU. Ultimately, the DISPROPRICUS study group published a comprehensive multicentre study showing an independent association between clinicians' intent to leave and the quality of the ethical climate in the ICU (Van den Bulcke et al. 2020). Therefore, interventions to reduce the plan to leave may be most effective when they focus on improving mutual respect and interdisciplinary reflection.

Engaging families in patients' care

For relatives, the opportunity to actively participate in ICU care may diminish feelings of powerlessness and decrease the chance of developing PICS-F after discharge. A recent paper (Dijkstra et al. 2023) included studies on family participation in essential care activities during ICU stay (participation free of obligation and left to the relatives' discretion). Identified themes on needs and perceptions were relatives' desire to help the patient, a mostly positive attitude among all involved, stress regarding patient safety, perceived beneficial effects, and relatives feeling in control. Patient and family opinions have even been considered when designing and implementing a weaning trial (Burns et al. 2017).

Nonetheless, research on relatives actively participating in essential care is limited (Olding et al. 2016), and how family participation should be performed is unknown. Furthermore, identified factors influencing active family engagement in care among critical care nurses (Hetland et al. 2017) were age, degree earned, critical care experience, hospital location, unit type, and staffing ratios. In this case, nursing workflow partially mediated the relationships between the intensive care unit environment and nurses' attitudes and between patient understanding and nurses' perspectives.

Visitation policies

Visitation policies in ICUs have evolved from very restrictive in the 1960s to more open (Milner 2023). Visitation allows patients to stay in touch with their family members and friends and be aware of events outside the hospital, positively affecting their condition (Escudero et al. 2016). During the pandemic, we also learned that using new technologies within the ICU is possible, bringing the virtual visit to the daily ICU work (Rose et al. 2021). Video communication is also helpful for information sharing and brief updates, aligning clinician and family perspectives.

An important issue regarding visitation is that the ICU is an emotionally taxing environment. Family members experience difficult emotions alongside their ill loved ones due to the intimidating and complex nature of the ICU, its restricted access, and the limited ability to interact with patients. Patient care is challenging, and the added demand to attend to the social needs of patients and their families may contribute to staff burnout (Ning and Cope 2020). For these reasons, facilitating the paramount role of visitation while simultaneously minimising any added burden on healthcare workers is crucial. An excellent example in this regard is the ICU bridge programme (Petrecca et al. 2022), which assigns volunteers (university students) to families. Volunteers acted as the bridge between families, staff, and patients, supporting both ends by representing the hospital staff (within the realms of their training) while keeping the non-medical needs of the patients and families.

Multi-component family support interventions

One of the main problems of PFCC is its implementation. PFCC programmes require multidisciplinary coordination beyond health professionals and must involve the hospital organisation and social policies at local and national levels. Recent studies (Wang et al. 2023; White et al. 2018) have assessed interventions delivered by the interprofessional ICU team that address both the affective and cognitive challenges that surrogate decision-makers experience. In the multicentre PARTNER trial, a low-cost intervention did not significantly affect the surrogates' burden of psychological symptoms at six months. Still, the surrogates' ratings of the quality of communication and the patient- and family-centredness of care were better, and the ICU LOS was shorter with the intervention than with usual care. Wang et al. (2023) systematically reviewed randomised family-centred interventions with family-centred outcomes in the adult intensive care unit (ICU). 67.3% of studies found improvements in at least one family-centred outcome, and 60% showed improvement when assessing the impact on mental health outcomes.

Currently underway, the FICUS trial (NCT05280691 (Naef et al. 2022) will test the clinical effectiveness and explore the implementation of a multi-component, nurse-led family support intervention in ICUs. The primary study endpoint is quality of family care, operationalised as family members' satisfaction with ICU care at discharge. Secondary endpoints will include quality of communication and nurse support, family management of critical illness (functioning, resilience), and family members' mental health (well-being, psychological distress) measured at admission, discharge, and after 3, 6, and 12 months.

Within multi-component family support interventions, we may also find strategies to mitigate PICS-F, especially on the caregiver burden (Torres et al. 2017). Family caregivers report impairments in quality of life during the first year after the patient's admission to the ICU (Alfheim et al. 2019; Milton et al. 2022). Moreover, greater severity of PTSD symptoms, explicitly numbing and re-experiencing symptoms experienced by patients and caregivers during neuro-ICU admission, was predictive of worse 3-month quality of life (Presciutti et al. 2021). It is imperative to consider screening and follow-up of caregivers for mental health problems, especially within the post-ICU programmes. Examples of studies focused on decreasing PICS-F are the assessment of psychological interventions on the mental health of ICU caregivers (Cairns et al. 2019; Ricou et al. 2020), the feasibility of implementing an app-based delivery of cognitive behavioural therapy to family members (Petrinec et al. 2021) or the development of a nurse-led intervention to support bereavement in relatives (van Mol et al. 2020).

What About Once Discharged?

One of the most critical limitations of the PARTNER trial was that it did not address events after discharge from the ICU that may have contributed to psychological distress, such as grief, financial strain, and the demands of caregiving. While family engagement throughout an ICU stay is central for patient healing, family members must also prepare to transition to post-discharge care. Caregivers face significant challenges, including the need to quit or change jobs and substantial economic hardships. Around 50-60% of caregivers of critically ill patients show depressive symptoms on patients' hospital discharge, and 43% reported symptoms one-year post-discharge (Cameron et al. 2016; Griffiths et al. 2013; Lobo-Valbuena et al. 2021). While many communication techniques mentioned above may mitigate the risk of developing PICS-F, families still need the emotional strength and skillset to care for their loved ones.

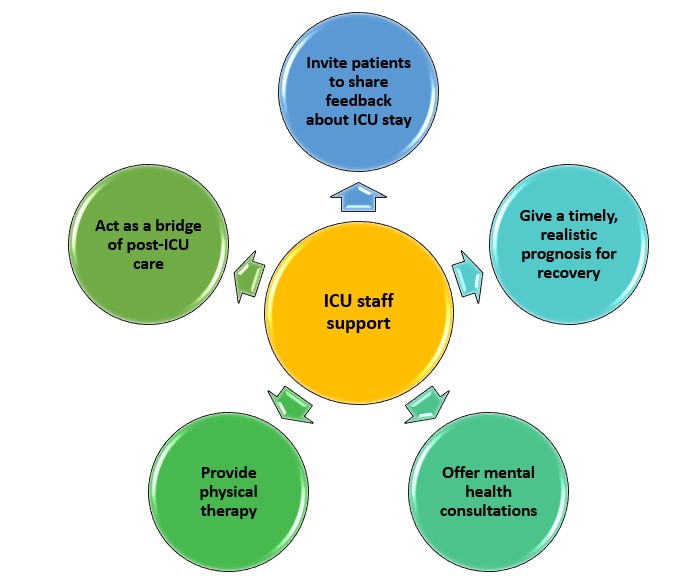

Active participation in care during the ICU admission may ease the transition home and make it less stressful for family members acting as the primary caregivers. Future interventions should be developed with much closer family member input, designed by considering key features such as involvement outcomes (communication, decision-making and satisfaction), health outcomes (family trauma and family well-being) and patient outcomes (Figure 3). The choice of intervention should be informed by a baseline diagnostic of family members' needs, readiness, and preparedness for involvement (Xyrichis et al. 2021).

Figure 3. ICU staff responsibilities within PFCC

What Remains to be Done?

Healthcare systems must engage patients and families primarily through patient and family advisory councils. We must foster a humanised environment for patients and families and value and respect our healthcare workers, addressing the burnout syndrome in ICU clinicians. Further attention is needed in three areas:

- in healthcare delivery: By being responsive to the preferences, needs, values, and cultural traditions of patients and families, PFCC may reduce inequities in critical care. We must study how healthcare disparities influence PFCC and explore how PFCC can promote health equity.

- and family engagement: We must consider engagement as a continuum, occurring at different levels and influenced by multiple factors that affect the willingness and ability of patients and families to engage.

- efforts to humanise the ICU workplace environment for the betterment of patients, families, and staff.

The ICU environment of the future will be designed to support the needs of patients and family members and mitigate their risks for PICS and PICS-F. Wearable technologies and home-based rehabilitation programmes will identify and alleviate these syndromes better. Future ICU design will distinguish between clinical and non-clinical areas to better integrate humanistic objects; the utmost setting will optimise physical, emotional, and mental well-being for the patient, family, and critical care team, shifting from a hostile environment into a home-like environment through architectural and interior design modifications. Mapping the impact of ICU design on patients, families, and the ICU team will be a challenge for future generations (Kesecioglu et al. 2012; Kotfis et al. 2022; Saha et al. 2022; Thompson et al. 2012; Vincent et al. 2017).

Finally, data regarding the experience of critically ill patients at high risk of death are scant. In a recent multiple-source multicentre study (Kentish-Barnes et al. 2023), a list of fifteen concerns was identified, encompassed in seven domains: worries about loved ones; symptom management and care (including team competence, goals of care discussions); spiritual, religious, and existential preoccupations (including regrets, meaning, hope and trust); being oneself (including fear of isolation and of being a burden, absence of hope, and personhood); the need for comforting experiences and pleasure; dying anddeath (covering emotional and practical concerns); and after death preoccupations. Identifying problems could allow clinicians to meet their needs better and align their end‐of‐life trajectory with their preferences and values.

Final Thoughts

The COVID-19 pandemic has once again highlighted the need for multidimensional care for the patient and the family and essential support for the healthcare professional.

PFCC is integral to high-quality health care and benefits patients, families, and clinicians. The highly technical nature of critical care puts patients and families at risk of dehumanisation and renders the delivery of PFCC challenging. Deliberate attention to respectful and humanising interactions with patients, families, and clinicians is essential. Optimal PFCC requires authentic engagement with patients and families of diverse backgrounds and experiences to inform quality improvement and research initiatives.

A better understanding of (1) the patient's needs and perceptions regarding family participation in essential care and (2) barriers that hinder a patient- and family‐centred environment can help. Insights into these aspects can guide interventions to implement or improve PFCC in the ICU. Besides, education and training of relatives and ICU healthcare providers are necessary to address safety and quality of care concerns, though most studies lack further specification. In addition, randomised controlled studies are needed to improve our understanding of the impact of PFCC in the intensive care setting.

We must work together to create a humanistic ICU environment for our patients and ourselves. It is time to include bioethics in our daily practice. It is time to transform the ICU into a friendly and respectful environment.

Acknowledgements

Our work as professionals dedicated to critically ill patients would not be what it is without the unconditional support of relatives and patients. They are why we wake up daily ready to care, learn and improve (albeit in tiny steps).

Conflict of Interest

F Gordo has performed consultancy work and formation for Medtronic. The other authors have no competing interests.

References:

Adelman RD, Tmanova LL, Delgado D et al. (2014) Caregiver burden: a clinical review. JAMA. 311(10):1052-1060.

Alfheim HB, Småstuen MC, Hofsø K et al. (2019) Quality of life in family caregivers of patients in the intensive care unit: A longitudinal study. Aust Crit Care. 32(6):479-485.

Alonso-Ovies Á, Heras la Calle G (2020) Humanizing care reduces mortality in critically ill patients. Med Intensiva (Engl Ed). 44(2):122-124.

Azoulay E, Sprung CL (2004) Family-physician interactions in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 32(11):2323-2328.

Beach MC, Topazian R, Chan KS et al. (2018) Climate of Respect Evaluation in ICUs: Development of an Instrument (ICU-CORE). Crit Care Med. 46(6):e502-e507.

Bidabadi FS, Yazdannik A, Zargham-Boroujeni A (2019) Patient's dignity in intensive care unit: A critical ethnography. Nurs Ethics. 26(3):738-752.

Bohart S, Møller AM, Andreasen AS et al. (2022) Effect of Patient and Family Centred Care interventions for adult intensive care unit patients and their families: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 69:103156.

Brown SM, Azoulay E, Benoit D et al. (2018) (2018) The Practice of Respect in the ICU. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 197(11):1389-1395.

Bruce J, McCue K (2018) Child life in the adult ICU: including the youngest members of the family. In G. Netzer (Ed.), Families in the Intensive Care Unit: A Guide to Understanding, Engaging, and Supporting at the Bedside (pp. 365-379). Springer.

Burns KEA, Devlin JW, Hill NS (2017) Patient and Family Engagement in Designing and Implementing a Weaning Trial: A Novel Research Paradigm in Critical Care. Chest. 152(4):707-711.

Cairns PL, Buck HG, Kip KE et al. (2019) Stress Management Intervention to Prevent Post-Intensive Care Syndrome-Family in Patients' Spouses. Am J Crit Care. 28(6):471-476.

Cameron JI, Chu LM, Matte A et al. (2016) One-Year Outcomes in Caregivers of Critically Ill Patients. N Engl J Med. 374(19):1831-1841.

Clark AP, Guzzetta CE (2017) A Paradigm Shift for Patient/Family-Centered Care in Intensive Care Units: Bring in the Family. Crit Care Nurse. 37(2):96-99.

Davidson JE (2009) Family-centered care: meeting the needs of patients' families and helping families adapt to critical illness. Crit Care Nurse. 29(3):28-34; quiz 35.

Davidson JE, Aslakson RA, Long AC et al. (2017) Guidelines for Family-Centered Care in the Neonatal, Pediatric, and Adult ICU. Crit Care Med. 45(1):103-128.

Davidson JE, Jones C, Bienvenu OJ (2012) Family response to critical illness: postintensive care syndrome-family. Crit Care Med. 40(2):618-624.

Davidson JE, Powers K, Hedayat KM et al. (2007) Clinical practice guidelines for support of the family in the patient-centered intensive care unit: American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004-2005. Crit Care Med. 35(2):605-622.

de la Fuente-Martos C, Rojas-Amezcua M, Gómez-Espejo MR et al. (2018) Humanization in healthcare arises from the need for a holistic approach to illness. Med Intensiva (Engl Ed). 42(2):99-109.

Dijkstra BM, Felten-Barentsz KM, van der Valk MJM et al. (2023) Family participation in essential care activities: Needs, perceptions, preferences, and capacities of intensive care unit patients, relatives, and healthcare providers-An integrative review. Aust Crit Care. 36(3):401-419.

Erçin-Swearinger H, Lindhorst T, Curtis JR et al. (2022) Acute and Posttraumatic Stress in Family Members of Children With a Prolonged Stay in a PICU: Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Trial. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 23(4):306-314.

Escudero D, Martín L, Viña L et al. (2016) It is time to change the visiting policy in intensive care units. Med Intensiva. 40(3):197-199.

Gazarian PK, Morrison CRC, Lehmann LS et al. (2021) Patients' and Care Partners' Perspectives on Dignity and Respect During Acute Care Hospitalization. J Patient Saf. 17(5):392-397.

Gerritsen RT, Hartog CS, Curtis JR (2017) New developments in the provision of family-centered care in the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 43(4):550-553.

Gerteis M-L, Daley J, Delbanco T (1993) Through the patient’s eyes: understanding and promoting patient-centered care. Jossey-Bass.

Goldfarb MJ, Bibas L, Bartlett V et al. (2017) Outcomes of Patient- and Family-Centered Care Interventions in the ICU: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit Care Med. 45(10):1751-1761.

Griffin T (2006) Family-centered care in the NICU. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 20(1):98-102.

Griffiths J, Hatch RA, Bishop J et al (2013) An exploration of social and economic outcome and associated health-related quality of life after critical illness in general intensive care unit survivors: a 12-month follow-up study. Crit Care. 17(3):R100.

Hetland B, Hickman R, McAndrew N, Daly B (2017). Factors Influencing Active Family Engagement in Care Among Critical Care Nurses. AACN Adv Crit Care. 28(2): 160-170.

Kang J (2023). Being devastated by critical illness journey in the family: A grounded theory approach of post-intensive care syndrome-family. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 78: 103448.

Kentish-Barnes N, Poujol AL, Banse E et al. (2023) Giving a voice to patients at high risk of dying in the intensive care unit: a multiple source approach. Intensive Care Med.

Kesecioglu J, Schneider MM, van der Kooi AW, Bion J (2012). Structure and function: planning a new ICU to optimize patient care. Curr Opin Crit Care. 18(6):688-692.

Kiwanuka F, Shayan SJ, Tolulope AA (2019) Barriers to patient and family-centred care in adult intensive care units: A systematic review. Nurs Open. 6(3):676-684.

Kotfi K, van Diem-Zaal I, Williams Roberson S et al. (2022) The future of intensive care: delirium should no longer be an issue. Crit Care. 26(1):200.

Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B et al. (2007) A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 356(5):469-478.

Lee HW, Park Y, Jang EJ, Lee YJ (2019) Intensive care unit length of stay is reduced by protocolized family support intervention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 45(8):1072-1081.

Lee LA, Carter M, Stevenson SB, Harrison HA (2014) Improving family-centered care practices in the NICU. Neonatal Netw. 33(3):125-132.

Lobo-Valbuena B, Sánchez Roca MD, Regalón Martín MP et al. (2021) Post-Intensive Care syndrome: Ample room for improvement. Data analysis after one year of implementation of a protocol for prevention and management in a second level hospital. Med Intensiva (Engl Ed). 45(8):e43-e46.

Long AC, Kross EK, Curtis JR (2016) Family-centered outcomes during and after critical illness: current outcomes and opportunities for future investigation. Curr Opin Crit Care. 22(6):613-620.

Ludmir J, Netzer G (2019) Family-Centered Care in the Intensive CareUnit-What Does Best Practice Tell Us? Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 40(5):648-654.

Lynn J (2014) Strategies to ease the burden of family caregivers. JAMA. 311(10):1021-1022.

Milner KA (2023) Evolution of Visiting the Intensive Care Unit. Crit Care Clin. 39(3):541-558.

Milton A, Schandl A, Larsson IM et al. (2022) Caregiver burden and emotional well-being in informal caregivers to ICU survivors-A prospective cohort study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 66(1):94-102.

Naef R, Filipovic M, Jeitziner MM et al. (2022) A multicomponent family support intervention in intensive care units: study protocol for a multicenter cluster-randomized trial (FICUS Trial). Trials. 23(1):533.

Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H et al. (2012) Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders' conference. Crit Care Med. 40(2):502-509.

Nin Vaeza N, Martin Delgado MC, Heras La Calle G (2020) Humanizing Intensive Care: Toward a Human-Centered Care ICU Model. Crit Care Med. 48(3):385-390.

Ning J, Cope V (2020) Open visiting in adult intensive care units - A structured literature review. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 56:102763.

Olding M, McMillan SE, Reeves S et al. (2016) Patient and family involvement in adult critical and intensive care settings: a scoping review. Health Expect. 19(6):1183-1202.

Petrecca S, Goin A, Hornstein D et al. (2022) The ICU Bridge Program: volunteers bridging medicine and people together. Crit Care. 26(1):346.

Petrinec A, Wilk C, Hughes JW et al. (2021) Delivering Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Post-Intensive Care Syndrome-Family via a Mobile Health App. Am J Crit Care, 30(6):451-458.

Presciutti A, Meyers EE, Reichman M, Vranceanu AM (2021) Associations Between Baseline Total PTSD Symptom Severity, Specific PTSD Symptoms, and 3-Month Quality of Life in Neurologically Intact Neurocritical Care Patients and Informal Caregivers. Neurocrit Care. 34(1):54-63.

Ricou B, Gigon F, Durand-Steiner E et al. (2020) Initiative for Burnout of ICU Caregivers: Feasibility and Preliminary Results of a Psychological Support. J Intensive Care Med. 35(6):562-569.

Rose L, Yu L, Casey J et al. (2021) Communication and Virtual Visiting for Families of Patients in Intensive Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A UK National Survey. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 18(10):1685-1692.

Rosenthal JL, Sauers-Ford HS, Williams J et al. (2021) Virtual Family-Centered Rounds in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Trial. Acad Pediatr. 21(7):1244-1252.

Saha S, Noble H, Xyrichis A et al. (2022) Mapping the impact of ICU design on patients, families and the ICU team: A scoping review. J Crit Care. 67:3-13.

Scheunemann LP, McDevitt M, Carson SS, Hanson LC (2011) Randomized, controlled trials of interventions to improve communication in intensive care: a systematic review. Chest. 139(3):543-554.

Seaman JB, Arnold RM, Scheunemann LP, White DB (2017) An Integrated Framework for Effective and Efficient Communication with Families in the Adult Intensive Care Unit. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 14(6):1015-1020.

Thompson DR, Hamilton DK, Cadenhead CD et al. (2012) Guidelines for intensive care unit design. Crit Care Med. 40(5), 1586-1600.

Todres L, Galvin K, Holloway I (2009) The humanization of healthcare: a value framework for qualitative research. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 4(2):68-77.

Torres J, Carvalho D, Molinos E et al. (2017) The impact of the patient post-intensive care syndrome components upon caregiver burden. Med Intensiva. 41(8):454-460.

Tzelepis F, Rose SK, Sanson-Fisher RW et al. (2014) Are we missing the Institute of Medicine's mark? A systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures assessing quality of patient-centred cancer care. BMC Cancer. 14, 41.

Valls-Matarín J, Del Cotillo-Fuente M (2022) Contents of the reception guide for relatives of Spanish intensive care units: Multicenter study. Med Intensiva (Engl Ed). 46(11), 654-657.

Van den Bulcke B, Metaxa V, Reyners AK et al. (2020) Ethical climate and intention to leave among critical care clinicians: an observational study in 68 intensive care units across Europe and the United States. Intensive Care Med. 46(1):46-56.

Van den Bulcke B, Piers R, Jensen HI et al. (2018) Ethical decision-making climate in the ICU: theoretical framework and validation of a self-assessment tool. BMJ Qual Saf. 27(10):781-789.

van Mol MMC, Wagener S, Latour JM et al. (2020) Developing and testing a nurse-led intervention to support bereavement in relatives in the intensive care (BRIC study): a protocol of a pre-post intervention study. BMC Palliat Care. 19(1):130.

Verma A, Maria A, Pandey RM et al. (2017) Family-Centered Care to Complement Care of Sick Newborns: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Indian Pediatr. 54(6):455-459.

Vincent JL, Slutsky AS, Gattinoni L (2017) Intensive care medicine in 2050: the future of ICU treatments. Intensive Care Med. 43(9):1401-1402.

Wang G, Antel R, Goldfarb M (2023) The Impact of Randomized Family-Centered Interventions on Family-Centered Outcomes in the Adult Intensive Care Unit: A Systematic Review. J Intensive Care Med. 8850666231173868.

White DB, Angus DC, Shields AM et al. (2018) A Randomized Trial of a Family-Support Intervention in Intensive Care Units. N Engl J Med. 378(25):2365-2375.

Wratney AT (2019) There Is No Place Like Home: Simulation Training for Caregivers of Critically Ill Children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 20(4):396-397.

Xyrichis A, Fletcher S, Philippou J et al. (2021) Interventions to promote family member involvement in adult critical care settings: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 11(4):e042556.

Zhang R, Huang RW, Gao X et al. (2018) Involvement of Parents in the Care of Preterm Infants: A Pilot Study Evaluating a Family-Centered Care Intervention in a Chinese Neonatal ICU. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 19(8):741-747.