At

first glance, America is making great strides toward a medical and

cultural shift in its approach to end-of-life care: More and more

providers are recognizing the benefits of hospice, more people are dying

at home, and many health care organizations are institutionalizing the

discussions between providers and patients that would help patients

formalize their wishes for end-of-life care through an advance

directive.

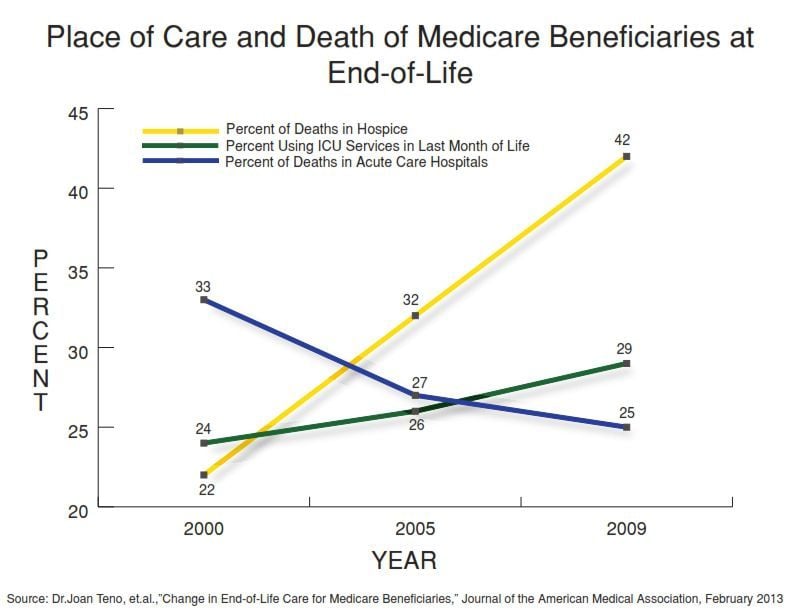

But pull up the curtain on these statistics, and the

drama that unfolds tells a very different story. End-of-life care

continues to be characterized by aggressive medical intervention and

runaway costs.

Like so many other problems plaguing the financing

and quality of health care in America, the end-of-life dilemma is

rooted in Medicare’s fee-for-service payment structure, says Joan M.

Teno, MD, lead author of a revealing study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in February.

The

study found that fewer individuals are dying in hospitals than in the

past and more are receiving hospice care. Yet more patients are

receiving care in an intensive care unit in their last month of life and

a growing number are shuffled around between different care sites in

their final 3 months.

“What you pay for is what you get,” Teno

said in an interview with JAMA after the study’s release. “There are

financial incentives to provide more care in fee-for-service care. We

don’t get paid to talk with patients about their goals or care or

probable outcomes of care. We do pay for hospitalizations, and there are

financial incentives for nursing homes to transfer patients back to

acute care.”

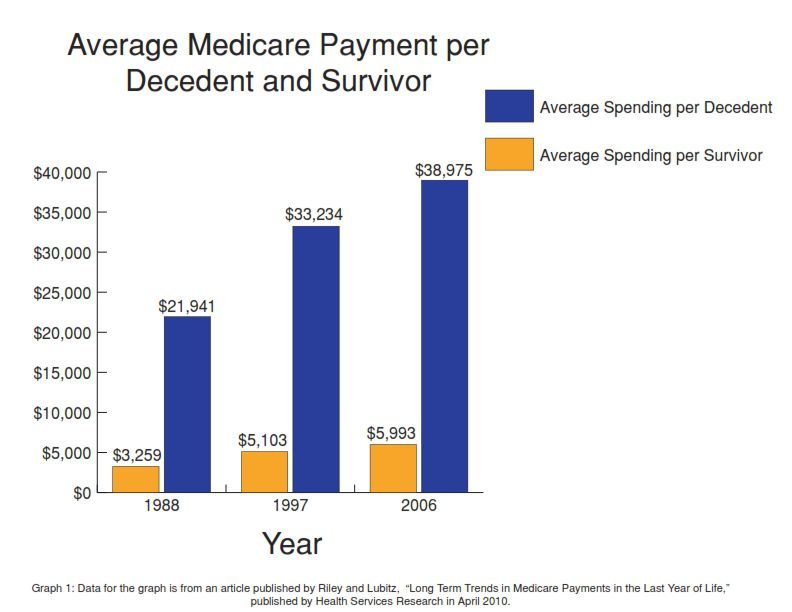

End-of-Life Care Costs

The

merits of increasingly aggressive treatment have been debated, but most

experts say that the use of multiple and intensive services at the end

of life is of little clinical benefit to the patient, and in many cases,

brings chaos and pain to what could otherwise be a peaceful dying

experience. Dr. Atul Gawande’s account, “Letting Go,” inThe New Yorker illustrates the heartbreaking effects of over treatment.

Gawande’s

story chronicles the medical care of Sara Monopi—a young woman

diagnosed with cancer who suffered through four rounds of chemotherapy,

radiation, numerous hospitalizations and at least two experimental

treatments, even though her doctors knew her condition was incurable.

Sara eventually succumbed to her death, but only after undergoing

expensive and unnecessary treatment that left her pained, exhausted and

eventually unconscious. Gawande writes, “Almost nothing we’d done to

Sara—none of our chemotherapy and scans and tests and radiation—had

likely achieved anything except to make her worse. She may well have

lived longer without it.”

Hospice physician Dr. Joanne Lynn

describes the current approach to end-of-life care as wasteful and

misdirected. Lynn, Director of the Center for Elder Care and Advanced

Illness at the Altarum Institute, a health systems research and

consulting organization, says per-capita costs will go down

significantly if we reduce the number of hospitalizations and procedures

Medicare beneficiaries endure during their last days.

“Right now

there’s nearly a blank check on Medicare-type costs,” Lynn said. “We

can have people go through extra imaging studies, we can have them go to

surgeries, we can have them go into hospitals over and over again. If

instead we mobilized services to their homes and greatly adapted the

services so that they really met people’s needs, we probably would use

hospitalization much less. We would use high-cost interventions and

imaging studies and diagnostic tests much less.”

Research supports Lynn’s observations. A 2009 Social Security Advisory Board report advocates

for a decrease in treatments and procedures that ultimately do not

benefit patients. The report states that research on Medicare costs and

services suggests that the government could achieve savings across the

health care spectrum by reducing the use of unnecessary medical services

that don’t actually improve beneficiaries’ health.

Others in the

field, such as Terry Berthelot, a senior attorney with the Center for

Medicare Advocacy and member of the National Council of Hospice and

Palliative Care Professionals, have voiced similar skepticism about the

over-use of medical services in end-of-life care.

“Currently,

the way we provide health care at the end of life is sort of crazy, only

focusing on the immediate problem rather than on the person,” Berthelot

said. “The health care system focuses on patching a person up and

sending her home when she shows up at the hospital. Long-term care plans

for the trajectory of a patient’s illness beyond the hospital doors are

often neglected. That kind of care is driving up our cost.”

Not only is it driving up costs, says Lynn, but Medicare’s

orientation toward hospitalization and excessive use of health services

at the end of life could cause a tragic setback in the fragile cultural

gains the United States has made in caring for its frail elderly.

When Lynn first started working in nursing homes in 1978, there were states where many frail and elderly patients were tied to their beds day in and day out. Since then, the way the United States treats the old and infirmed has improved.

As the baby boomer population ages into

Medicare, which is already suffering from its own poor financial health,

the consequent rising health care costs could break the back of our

nation’s long-term care system. Unless we change the way we approach

care management for those nearing the end of life, she says, we could

easily slip back to the darker days of nursing home care.

"We

will either bankrupt families and communities and the nation as a whole,

or we will learn to walk out on people. The better course would be to

try to find highly efficient ways to take care of one another in a

reliable way," she said. "Are we really going to learn to just warehouse

people again, tie them down to the bed, just ignore pressure ulcers,

ignore liberty and choice? Now is the time to do one step better. The

better has to be more efficient. It can’t just run up the costs."

Containing Costs by Planning for the End

Research

has shown that planning ahead for end-of-life care through advance

directives, which allow patients, if they are incapacitated, to specify

ahead of time what actions should be taken regarding their treatment,

could reduce spending. The use of advance directives specifying

end-of-life care limitations led to significantly lower levels of

Medicare spending in geographic regions that had had relatively high

end-of-life costs, according to a 2011 study published in The Journal of the American Medical Association.

Berthelot

recommends that doctors receive training regarding how to carry on

discussions about end-of-life treatment decisions starting when the

patient is young and healthy, framing it so that the focus is on quality

of life and giving the patient the kind of care that they want. “Honesty in conversation, rather than constantly focusing just on what

the next medical procedure will be, would make a huge difference for

the kind of care people get, that they get to make real choices about

that kind of care,” she said.

Providers should engage in ongoing,

meaningful conversations with patients when they’re healthy about what

matters to them when it comes to the care they receive as they near the

end of life, she said.

Director of Research for the Hospice and

Palliative Care Nurses Association June Lunney agreed that doctors and

patients need to have conversations about end-of-life care so that

seniors can make informed decisions about the treatments they do or

don't want to receive. Lunney helped develop the support from the

National Institutes on Health for research on end-of-life issues and

worked at the RAND Corporation's Center for End-of-Life Care.

Berthelot says advance directives could be the holy grail of America’s end-of-life crisis.

“They

can save our system a great deal of money because currently folks are

getting all types of end-of-life care that’s very, very expensive that

doesn’t in any way save lives. It only prolongs life at a huge cost with

very, very little real benefit because of all of the misery at the end

of life when somebody’s dying in a hospital,” she said.

Is Hospice the Answer?

Hospice

care toward the end of life often helps people live longer, Berthelot

said. “A big part of that is the fact that they don’t bounce back and

forth between home and the hospital and the skilled nursing facility and

that their care is being managed,” she said. “Good hospice care is an

example of seeing the person as the unit of care, rather than the

illness. The focus is on the whole person…the focus is on quality of

life.”

There is a rise in the use of hospice care. Medicare

beneficiaries’ use of hospice services has nearly doubled over the past

decade, according to a 2012 MedPAC report.

In 2010, 44 percent of beneficiaries who died that year used hospice,

an increase from 23 percent in 2000. But again, these numbers depict a

false sense of progress.

Among the Medicare beneficiaries in

Teno’s study, more than a quarter were in hospice care for less than 3

days-not nearly long enough to realize the benefits of the program. And

among the patients referred to hospice late, more than 40 percent were

hospitalized and spent time in the intensive care unit prior to

referral.

Lunney echoed the concerns raised by the JAMA study.

She says that short hospice stays don’t lead to better quality of life

for patients in their last days.

“We don’t know what the ideal

length of stay is, but less than seven days is not enough time. Putting

people into hospice care at the last minute doesn’t allow time for

providers to manage the patients’ symptoms well,” she said.

The

median hospice stay length hasn’t changed significantly over the past

decade, Harvard Medical School professor David G. Stevenson wrote in a

2012 article in The New England Journal of Medicine. The

median stay only rose from 17 days in 2000 to 18 days in 2010,

reflecting the fact that a sizable minority of beneficiaries goes into

hospice care mere days before their deaths, Stevenson wrote.

Lynn said that the hospice model, while it laudably improves the quality of the dying experience, may not be the panacea of cost-savings Medicare needs. In fact, she says, increased use of hospice may actually end up contributing to the cost quandary afflicting end-of-life care because the benefit hasn’t been adapted to deal with the clinical picture of today’s dying.

She said the issue is that the hospice care model

is built around patients who are rapidly declining, rather than the

patients she classifies as the “frail population”: those with multiple

chronic conditions and ambiguous prognoses.

“For someone whose

main problem is dementia, the hospice design was not well adapted,” she

said. “It may even increase the costs because the timing of death is

quite unpredictable. Lots of people will end up having to be discharged

from hospice after having used many months of what is a pretty high-cost

intervention.”

The population that hospice care serves has

changed significantly since the advent of the Medicare benefit for it,

according to Stevenson’s article. In 1990, 16 percent of Medicare

hospice care recipients had non-cancer diagnoses. As of November 2012,

it was more than two-thirds, rather than conditions such as heart

failure and dementia, Stevenson wrote.

Lynn says hospice is part

of the solution to the U.S. health care system’s end-of-life care

issues, but it’s going to need some redesign first. Nevertheless, Lynn

believes it’s imperative that the country figure out and enact the

solution to the end-of-life care model’s issues, or Americans will face a

choice between bankrupting themselves or abandoning their elders.

Source: Medicare NewsGroup