The role of the ICU social worker

End-of-life issues occur frequently in the intensive care unit (ICU). The specific training and skills received by social workers provides them with the necessary tools to collaborate with the interdisciplinary team and provide holistic care to the patient and family. Research has shown that there is great variation in the level of participation of the social worker, often because they do not have a formal role. We examine the stressors impacting patients, family members and staff in the ICU, the various roles that social workers can play and provide a construct for how the ICU social worker can be an integral member of the critical care team.

Social work’s role in end-of-life care in the intensive care unit (ICU) varies widely across and within hospitals. Social workers can be a valuable asset in the provision of end-of-life care. They are trained to provide support to patients and families, improve communication between medical providers and patient/family, advocate for their wishes as well as being attuned to cultural needs (Eicholz Heller and Jimenez-Bautista 2015; Saunders et al. 2015). Where the ICU team is generally busy and time constrained, the social worker can take the necessary time to listen, educate and advocate for the patient and family as well as serve as a bridge between the patients, families and medical team. Yet, despite all of these advantages, social workers in many institutions do not have a formal role in the ICU (Gonzalez 2013).

Demographics and the ‘cost’ of ICU care at end of life

“Approximately 10% of patients admitted to the ICU will die in or shortly after they leave the ICU” (McCormick 2011, p. 54). Statistically, 20% of all deaths in the United States occur in ICUs (Curtis 2005; Gries et al. 2008). Between 11.5% and 30% of U.S. hospital cost is in the ICU, and roughly half of the patients who have a length of stay longer than 14 days in the ICU eventually die (Rose and Shelton 2006). In the ICU as many as 95% of the patients are incapacitated due to illness or sedation (McCormick et al. 2007; Truog et al. 2008), which results in the family making treatment decisions and participating in goals of care discussions with the critical care clinicians (Curtis and Vincent 2010; Rose and Shelton 2006). Due to biomedical advances and technical skills, patients’ lives are often extended, which can lead to prolonged suffering (Christ and Sormanti 1999).

ICU environment stressors

Admissions to the ICU are often decided by non-critical care physicians and many times are unexpected and emergent (Delva et al. 2002). Additionally, end-of-life care is frequently not discussed with patients or families prior to the decision to admit to intensive care (Rady and Johnson 2004). This can create a level of tension between the ICU team and the family, patient and prior medical team. Critical care physicians are often unfamiliar with a patient’s prior medical history, do not have an existing relationship with the patient and family and hence are not fully prepared to discuss end-of-life decisions. This can lead to a medical treatment plan that is incongruent with the patient’s wishes.

In the ICU, there are many providers involved in each patient’s care. This can lead to conflicting and confusing information being relayed to the patient and family. Additionally, because the ICU is a complex environment, levels of stress, anxiety and depression increase. Additionally, death is a deeply personal experience and each individual interprets the event very differently depending on their cultural and religious backgrounds and life experiences. For, example, someone with strong Catholic beliefs may be unable to accept the futility of ongoing life support, despite no chance of survival.

Also contributing to stress, families must balance managing their life outside of the ICU, including such responsibilities as: caring for children, paying bills, going to work, and at the same time caring for and supporting their dying loved one (Abbott et al. 2001). This results in caregiver burden, and can impact their ability to understand and interpret medical information provided, the decline of their loved one, and can escalate conflicts with the medical team. Families often feel stress, confusion, depression and helplessness. Many suffer from symptoms of acute stress disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or posttraumatic stress reaction (Carlet et al. 2003; McAdam and Puntillo 2009; McAdam et al. 2010). Family members in ICUs are usually in a state of crisis (Delva et al. 2002; Mann et al. 1977) and feel unprepared to act as the patient’s decision maker (Rose and Shelton 2006). These factors can affect their treatment decisions for the patient as well as their satisfaction with the quality of care received in the ICU (Abbot et al. 2001).

Role of ICU social worker with patient and family

ICU social workers play a key role in end-of-life care, acting as case managers, counsellors, teachers, mediators and advocates (Bomba et al. 2010; Csikai 2006). They are trained to work with the whole person, and understand diverse cultural, ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds (Heyman and Gutheil 2006; Saunders et al. 2015). Master-level social workers receive training in the foundational skills needed to engage, assess and intervene through the use of critical thinking, active listening and strong communication skills. They are also trained in more advanced skills such as crisis intervention, strengths perspective, cognitive restructuring, person-in-environment as well as individual and family therapy (Hartman-Shea et al. 2011; Kondrat 2013).

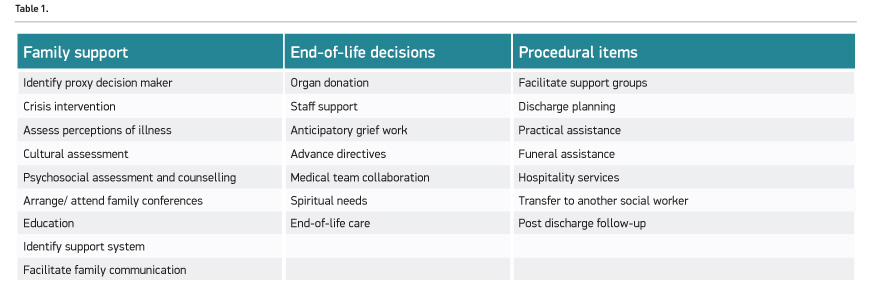

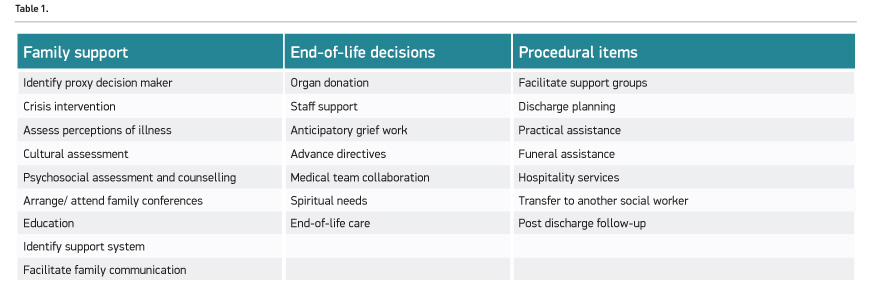

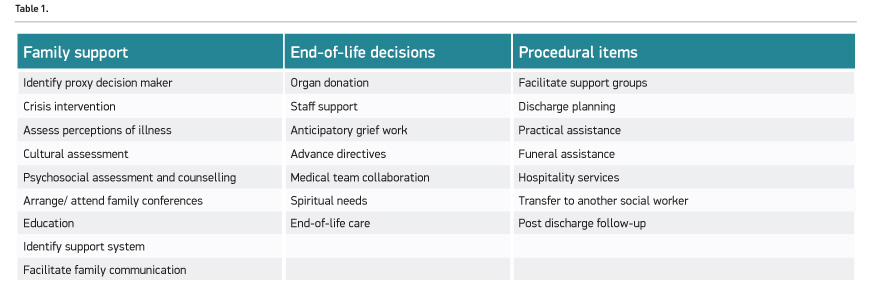

Social workers can help families navigate the ICU environment through understanding how it functions and the roles of the staff involved in the care of the patient (McCormick et al. 2010; Rose and Shelton 2006). “Families require accurate, clear, and timely information presented in a language that invites a beginning integration not only of the issues at hand but also of the potential outcomes” (McCormick 2011, p. 54). Social workers develop coping skills with families to deal with the stressful environment, clarify medical information regarding prognosis, decision-making options (e.g. do not resuscitate, artificial hydration/nutrition, mechanical ventilation, antibio-tics, renal dialysis, etc.), and the difference between supportive/comfort care and life-maintaining care (Heyman & Gutheil 2006; McCormick et al. 2010). Hartman-Shea et al. (2011) found that psychosocial counselling and support was one of the most frequent social work activities most linked to family satisfaction and the reduction of anxiety. The social worker has the ability to assist with those needs through spending time with families to review the medical information and process their emotions. Assessments are crucial in the ICU team’s ability to partner and work with families. The ICU social worker is able to assess how the family responds to crisis situations, the family dynamics and their communication patterns, which aids the medical team in providing a more empathic, compassionate and effective means to communicate with the family (Hartman-Shea et al. 2011). It is imperative that families of ICU patients understand and are aware of the different end-of-life care options; including how and where the patient’s death can occur and the process surrounding the death in order to make decisions congruent with the patients’ wishes (McCormick et al. 2007). Hartman-Shea et al. (2011) identified twenty-four medical social work interventions (Table 1).

Social workers are often the most knowledgeable and comfortable discussing end-of-life care and hospice choices. They can guide the family and patient in understanding and making meaning of the different end-of-life options appropriate and available, as well as what each of those options means to the patient and family through an examination of the potential benefits or burdens (Csikai 2006, p. 1307). The social worker fills in the gaps that ICU medical providers may leave for families, working as ‘context interpreters’ for family members (Cagle and Kovacs 2009). The ICU social worker is able to help the families take the most important and relevant information and put it into context while also working through the feelings and reactions families have from this information (Cagle and Kovacs 2009). Due to their work with families, social workers decrease family members’ feelings of helplessness in the ICU (Miller et al. 2007) as well as their acute stress.

Role of social worker on interdisciplinary team

Cagle and Kovacs (2009) and McCormick and colleagues (2010) stress the significant impact social workers have on improved communication between patients, families and healthcare providers. Social workers spend time speaking with families directly, discussing the family’s perspective on the patient’s condition, clarifying information, organising and attending family conferences and providing relevant psychosocial information to the ICU medical team (Rose and Shelton 2006). ICU clinicians are trained to assess and treat critically ill patients. Their bias is to treat and support, which can, in some instances, lead to futile treatment, prolonged ICU stays and patient and family suffering. The social worker can advocate for the patient and, as the palliative care literature clearly demonstrates, improve adherence to patient/family wishes and outcomes (May et al. 2015; Cassel et al. 2010). Social workers “can encourage health professionals to understand and clarify their own role in the decision-making process, promote communication and problem solving, and identify and improve systems that may interfere with optimal communication and problem solving regarding such sensitive problems as end-of-life decisions” (Werner et al. 2004, p. 34).

Family conferences are an effective strategy for medical providers to discuss end-of-life care and have been linked to the reduction of the family’s symptoms of PTSD, anxiety and depression (Browning 2008; McAdam and Puntillo 2009). The social worker plays a key role in family conferences, from arranging the meeting to ensuring that the key family members are present and available for the meeting, as well as acting as a context interpreter and clarifier during the meeting. The social worker can provide support to the family after the meeting.

Conclusion

“Social work in the ICU has become a subspecialty of medical social work just as the ICUs themselves have become more specialized” (McCormick 2011, p. 55). Presently, there is great variability in the way social work is included on the care team across ICUs and hospitals. The formal inclusion of social work on the ICU team provides invaluable additions to the holistic care of critically ill patients and their families. Through the application of skills in stress management, cultural competency, identifying caregiver burden, as well as employing their training in addressing critical decisions and end-of-life care, social workers improve patient/family experience, decision making and outcomes of care.

Conflict of interest

Allison Gonzalez declares that she has no conflict of interest. Robert Klugman declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

ICU Intensive care unit

Abbott K, Sago J, Breen CET et al. (2001) Families looking back: one year after discussion of withdrawal or withholding of life-sustaining support. Crit Care Med, 29: 197-201.

Bomba P, Morrissey M, Leven D (2010) Key role of social work in effective communication and conflict resolution process: medical orders for life-sustaining treatment (MOLST) program in New York and shared medical decision making at the end of life. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care, 7, 56-82.

Browning A (2008) Empowering family members in end-of-life care decision making in the intensive care unit. Dimens Crit Care Nurs, 28(1): 1-23.

Cagle J, Kovacs P (2009) Education: a complex and empowering social work intervention at the end of life. Health Soc Work, 34(1): 17-27.

Carlet J, Thijs L, Antonelli M et al. (2003) Challenges in end-of-life care in the ICU: statement of the 5th international consensus conference in critical care. Intensive Care Med, 30: 770-84.

Cassel JB, Kerr K, Pantilat S et al. (2011) Does palliative care consultation reduce ICU length of stay. J Pain Symptom Manage, 41(1): 191-2.

Christ G, Sormanti M (1999) Advancing social work practice in end-of-life care. Soc Work Health Care, 30(2): 81-99.

Csikai EL (2006) Bereaved hospice caregivers’ perceptions of the end-of-life care communication process and the involvement of health care professionals. J Palliat Care, 9(6): 1300-9.

Curtis R (2005) Interventions to improve care during withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments. J Palliat Med, 8: 116-31.

Curtis R, Vincent JL (2010) Ethics and end-of-life care for adults in the intensive care unit. Lancet, 376: 1347-53.

Delva D, Vanoost S, Bijttebier P et al. (2002) Needs and feelings of anxiety of relatives of patients hospitalized in intensive care units: implication for social work. Soc Work Health Care, 35(4): 21-40.

Eicholz Heller F, Jimenez-Bautista A (2015) Building a bridge to connect patients to their homeland at end of life. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care, 11: 96-100.

Gonzalez A (2013) How do social workers in the ICU perceive their role in providing end-of-life care? What factors impede or help them in carrying out this role in end-of-life care and is social work education a contributing component? (Unpublished doctoral dissertation) University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. [Accessed: 15 March 2018] Available from repository.upenn.edu/edissertations_sp2/46/

Gries C, Curtis R, Wall R et al. (2008) Family member satisfaction with end-of-life decision-making in the intensive care unit. Chest, 3: 704-12.

Hartman-Shea K, Hahn A, Kraus J et al. (2011) The role of the social worker in the adult critical care unit: a systematic review of the literature. Soc Work Health Care, 50: 143-57.

Heyman J, Gutheil I (2006) social work involvement in end of life planning. J Gerontol Soc Work, 47(3/4): 47-61.

Kondrat ME (2013) Person-in-environment. In: Encyclopedia of social work. National Association of Social Workers Press and Oxford University Press. DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780199975839.013.285

Mann JK, Durgin JS, Atwood J (1977) The social worker on the critical care team. Supervisor Nurse, 8(9): 62-8.

May P, Garrido MM, Cassel JB et al. (2015) Prospective cohort study of hospital palliative care teams for inpatients with advanced cancer: earlier consultation is associated with larger cost-saving effect. J Clin Oncol, 33(25): 2745-52.

McAdam J, Puntillo K (2009) Symptoms experienced by family members of patients in intensive care units. Am J Crit Care, 18: 200-9.

McAdam J, Dracup K, White D et al. (2010) Symptom experiences of family members of intensive care unit patients at high risk of dying. Crit Care Med, 38(4): 1078-85.

McCormick A (2011) Palliative social work in the intensive care unit. In: Altilio T,

Otis-Green S, eds. Oxford textbook of palliative social work. New York: Oxford University Press, pp.53-62.

McCormick A, Curtis R, Stowell-Weiss P et al. (2010) Improving social work in intensive care unit palliative care: Results of a quality improvement intervention. J Palliat Med, 13(3): 297-304.

McCormick A, Engelberg R, Curtis, R (2007) Social workers in palliative care: assessing activities and barriers in the intensive care unit. J Palliat Care Med, 10: 929-37.

Miller J, Frost M, Rummans T et al. (2007) Role of a medical social worker in improving quality of life for patients with advanced cancer with a structured multidisciplinary intervention. J Psychosoc Oncol, 25(4): 105-19.

Rady M, Johnson D (2004) Admission to intensive care unit at the end-of-life: is it an informed decision? Palliat Med, 18: 705-11.

Rose S, Shelton W (2006) The role of social work in the ICU: reducing family distress and facilitating end-of-life decision-making. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care, 2(2): 3-23.

Saunders JA, Haskins M, Vasquez M (2015) Cultural competence: a journey to an elusive goal, J Soc Work Educ, 51(1): 19-34.

Truog R, Campbell M, Curtis R et al. (2008) Recommendations for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: s consensus statement by the American College of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med, 36(3): 953-63.

Werner P, Carmel S, Ziedenberg H (2004) Nurses’ and social workers’ attitudes and beliefs about and involvement in life-sustaining treatment decisions. Health Soc Work, 29(1): 27-35.