ICU Management & Practice, Volume 16 - Issue 2, 2016

The Final Link

The "Chain of Survival" Concept After Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest

To overcome a time-sensitive and severe condition with a low survival rate—out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA)—the following four links of the “chain of survival” concept were introduced by Newman in the 1980s (Newman 1989):

- Early access to emergency medical care;

- Early cardiopulmonary resuscitation;

- Early defibrillation; and

- Early advanced cardiac life support.

The American Heart Association (AHA) and the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation adopted this concept in their guidelines in the early 1990s. Thereafter a similar concept was used globally until the publication of guidelines in 2005 (ECC Committee, Subcommittees and Task Forces of the American Heart Association 2005).

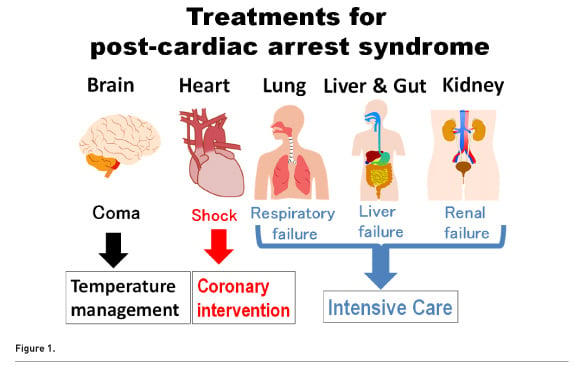

Even after spontaneous circulation is restored, most patients die within 2 days (Neumar et al. 2008). Post-cardiac arrest syndrome is a severe medical condition caused by prolonged complete whole-body ischaemia and reperfusion; thus the management of patients with post-cardiac arrest syndrome is challenging. Early arterial hypotension is common and associated with increased in-hospital mortality (Chang et al. 2007; Negovsky 1972). In addition to haemodynamic instability, pulmonary dysfunction is also common after cardiac arrest (Neumar et al. 2008). During this critical condition, several treatments are required to improve the outcome of cardiac arrest, including therapeutic hypothermia (targeted temperature management), percutaneous coronary intervention and other advanced interventions (Fig. 1).

Thus the European Resuscitation Council revised the final link in the chain-of-survival concept from “early advanced cardiac life support” to provision for “post-resuscitation care” in 2005 (Nolan 2005). In 2010 the AHA guidelines implemented a “fifth link,” which is “post-cardiac arrest care,” in addition to the previous four links, as another critical link in the chain-of-survival concept (Peberdy et al. 2010). Although the introduction of the final link of the “chain-of-survival” concept was a rational approach, no direct evidence supported its implementation at the time of the publication of the guidelines (Peberdy et al. 2010; Nolan 2005).

Aizu Chain-of-Survival ConceptCampaign: From a Case to a ClinicalStudy

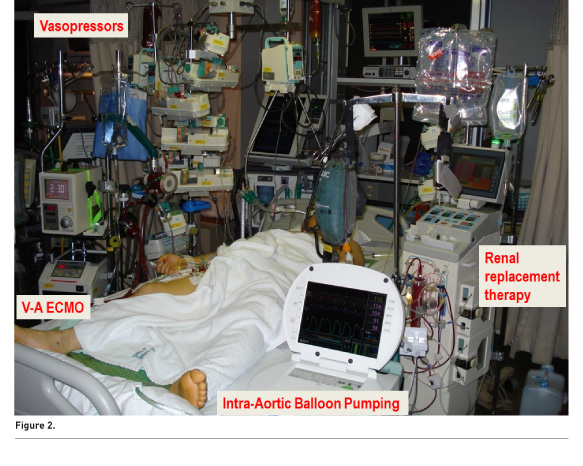

In spring 2008, a 58-year-old man suddenly lost consciousness and had a cardiac arrest. His wife immediately called emergency medical services and began chest compression. The emergency medical services provider found that he had ventricular fibrillation and performed defibrillation, which was unsuccessful. Our medical team participated in the resuscitation in progress and performed advanced cardiac life support, including adrenaline administration and intubation. We strictly followed the 2005 AHA Guidelines, which were the latest available at that time. However, it took 2.5 hours to achieve return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC). Immediately after achieving ROSC, his blood pressure decreased again in the emergency department. At that time, no consensus has been reached on the optimal treatment for post-cardiac arrest patients in our hospital. However, we provided what we believe was the most appropriate treatment for our patient (Fig. 2). Soon after the return of spontaneous circulation, he developed shock despite large doses of catecholamines. We therefore used venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and an intra-aortic balloon pumping system with continuous renal replacement therapy. I spent several days and nights with him in the intensive care unit (ICU). After a month of aggressive intensive care in the ICU, he was discharged from our hospital with favourable neurological status.

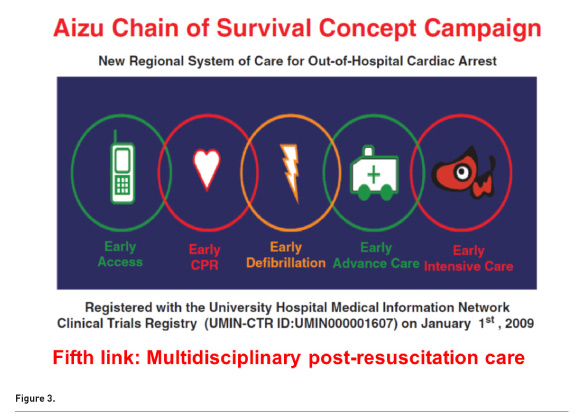

The present case clarified two things. First, even if 150 minutes have passed before ROSC is achieved, the brain may not be completely impaired if the early links of the chain of survival are well conducted. Second, high-quality and aggressive ICU management is needed to counteract post-cardiac arrest syndrome. During the patient’s treatment the question “Could these treatments be performed outside the ICU?” arose, for which the answer is no. This led to the clinical question “Can patient outcomes improve if all patients with postcardiac arrest syndrome in this region are treated at a single ICU?” To answer this clinical question, we performed a region-wide multicentre prospective study, the Aizu Chain of Survival Concept Campaign, to evaluate the effect of the final link in the chain of survival, which was defined as multidisciplinary postresuscitation care (Fig. 3) (Tagami et al. 2012).

The Aizu region (Fukushima, Japan) is a suburban/rural area with 300,000 residents. All 12 emergency hospitals (one tertiary care and 11 non-tertiary care hospitals) in the region participated in the study. After the patients with OHCA achieved ROSC at each hospital, they were concentrated in one tertiary care hospital and treated aggressively to focus on the fifth link. We used an advanced haemodynamic monitoring system (PiCCO monitoring system, PULSION, Germany) to measure several important haemodynamic and pulmonary variables for all the patients. The PiCCO system provides cardiac output and global end-diastolic volume as volumetric haemodynamic variables. It also provides extravascular lung water, which represents the degree of pulmonary oedema, and the pulmonary vascular permeability index, which can be used to differentiate between cardiogenic and non-cardiogenic pulmonary oedema. We performed individualised treatment, and optimised haemodynamic and respiratory instability by using these advanced variables, because every single patient has different cardiac function, fluid status, vascular permeability and previous medical history (including time from collapse to ROSC). After implementation of the fifth link, the proportion of survivors with a favourable neurological outcome increased significantly, and the fifth link was found to be an independent factor for a favourable neurological outcome (Tagami et al. 2012).

Post-Resuscitation Care and Outcomes:Recent Evidence

The last decade has witnessed a significant reduction in OHCA-related mortality rate worldwide (SOS-KANTO 2012 Study Group 2015; Fugate et al. 2012; Wissenberg et al. 2013). Several large nationwide studies have suggested that the improvement in outcomes may be related to the provision of post-resuscitation care in addition to the improvement of the actions of bystanders and treatments before the ROSC (van der Wal et al. 2011; Fugate et al. 2012; Tagami et al. 2016; Kim et al. 2013). Fugate et al. reported that the in-hospital mortality rate of patients with cardiac arrest in the United States decreased by 11.8% from 2001 to 2009, based on the analysis of the American National Inpatient Sample database (Fugate et al. 2012). Van der Wal et al. reported that inducing a mild therapeutic hypothermia was associated with a 20% relative reduction in OHCA-related in-hospital mortality in the Netherlands (van der Wal et al. 2011). Kim et al. from Korea reported that provision of post-resuscitation care resulted in a significant improvement in patient outcome, and concluded that the systematic inclusion of the fifth link is recommended for improving patient outcomes (Kim et al. 2013). We recently reported that the provision of therapeutic hypothermia and percutaneous coronary intervention increased significantly among cardiogenic OHCA cases related to ventricular fibrillation over the period 2008 to 2012 in Japan (Tagami et al. 2016).We found that in-hospital mortality decreased significantly over the 5-year period. The results of logistic regression analyses using multiple propensity score analyses suggested that the decrease in mortality can be explained by the increase in the provision of both therapeutic hypothermia and percutaneous coronary intervention (Tagami et al. 2016).

Several studies have suggested that the level of care provided by institutions (i.e. tertiary care, level 1 vs. non-tertiary care, level 2 or 3) affects the outcome in post-resuscitation patients (Kajino et al. 2010; Soholm et al. 2015; Soholm et al. 2013; Stub et al. 2011). Among OHCA patients without field ROSC in Japan, those who were transported to tertiary-care centres had better survival than those transported to non-tertiary-care centres (Kajino et al. 2010). Similar results were reported from Denmark (Soholm et al. 2013; Soholm et al. 2015). Schober et al. evaluated the association among patient-related factors, comorbidities and intensive care measures and their impact on the outcome for patients treated after cardiac arrest in 87 Austrian ICUs (Schober et al. 2014). They reported that the high frequency of post-cardiac arrest care at an ICU seemed to be associated with improved outcome of patients who had a cardiac arrest (Schober et al. 2014). These studies suggest that admission to high-level-of-care centres and intensive care administration after OHCA are associated with a significantly higher survival rate even after adjustment for prognostic factors including pre-arrest comorbidity (Kajino et al. 2010; Soholm et al. 2015; Soholm et al. 2013; Stub et al. 2011; Schober et al. 2014).

Relay Baton of Survival

Recent evidence apparently indicates that the initial links before achieving ROSC are critically important. The final link can be initiated only if the previous links in the chain are well connected and patients achieved ROSC. Each link in the chain of survival could be represented as a relay baton. Therefore a relay baton should not be dropped before the final runner. However, if the baton is passed to the final runner, that specialist should perform as well as possible to achieve the goal of treatment. Our goal is not only to achieve spontaneous circulation but also to restore the patient’s previous quality of life. Thus the true goal is located after completion of the final link. An emergency department physician must start the final link immediately after the patient achieves ROSC. Intensivists, cardiologists, neurocritical care physicians, nurses, medical engineers and all providers working in the ICU have the responsibility to complete the final chain in the survival link.

Conclusions

Several large nationwide studies have suggested that recent improvements in outcome are associated with the provision of post-resuscitation care. Recent studies also showed that admission to ICUs in high-level-of-care centres and administration of aggressive intensive care after OHCA were associated with better outcomes. Although randomised trials have not yet been performed, providing aggressive post-cardiac arrest care is a reasonable approach.

Conflict of Interest

Takashi Tagami declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

AHA American Heart Association

ICU intensive care unit

OHCA out-of-hospital cardiac arrest

ROSC return of spontaneous circulation

References:

Chang WT, Ma MH, Chien KL et al. (2007) Postresuscitation myocardial dysfunction: correlated factors and prognostic implications. Intensive Care Med, 33(1): 88-95. PMID: 17106656 PubMed ↗

ECC Committee, Subcommittees and Task Forces of the American Heart Association (2005) 2005 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation, 112(24 Suppl):IV1-203. PMID: 16314375 PubMed ↗

Fugate JE, Brinjikji W, Mandrekar JN et al. (2012) Post-cardiac arrest mortality is declining: a study of the US National Inpatient Sample 2001 to 2009. Circulation, 126(5): 546-50. PMID: 22740113 PubMed ↗

Kajino K, Iwami T, Daya M et al. (2010) Impact of transport to critical care medical centers on outcomes after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation, 81(5): 549-54.

PMID: 20303640 PubMed ↗

Kim JY, Shin SD, Ro YS et al. (2013) Post-resuscitation care and outcomes of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a nationwide propensity score-matching analysis. Resuscitation, 84(8): 1068-77.

PMID: 23454438 PubMed ↗

Negovsky VA (1972) The second step in resuscitation--the treatment of the 'post-resuscitation disease'. Resuscitation, 1(1): 1-7. PMID: 4653025 PubMed ↗

Neumar RW, Nolan JP, Adrie C et al. (2008) Post-cardiac arrest syndrome: epidemiology, pathophysiology, treatment, and prognostication. A consensus statement from the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (American Heart Association, Australian and New Zealand Council on Resuscitation, European Resuscitation Council, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, InterAmerican Heart Foundation, Resuscitation Council of Asia, and the Resuscitation Council of Southern Africa); the American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee; the Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; the Council on Cardiopulmonary, Perioperative, and Critical Care; the Council on Clinical Cardiology; the Stroke Council. Circulation, 118(23): 2452-83.

PMID: 18948368 PubMed ↗

Newman M (1989) The chain of survival concept takes hold. JEMS, 14: 11–3.

Nolan J, European Resuscitation Council (2005) European Resuscitation Council guidelines for resuscitation 2005. Section 1. Introduction. Resuscitation, 67 Suppl 1: S3-6. PMID: 16321715 PubMed ↗

Peberdy MA, Callaway CW, Neumar RW et al. (2010) Part 9: post-cardiac arrest care: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation, 122(18 Suppl 3): S768-86.

PMID: 20956225 PubMed ↗

Schober A, Holzer M, Hochrieser H et al. (2014) Effect of intensive care after cardiac arrest on patient outcome: a database analysis. Crit Care, 18(2): R84.

PMID: 24779964 PubMed ↗

Søholm H, Kjaergaard J, Bro-Jeppesen J et al. (2015) Prognostic implications of level-of-care at tertiary heart centers compared with other hospitals after resuscitation from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes, 8(3): 268-76.

PMID: 25944632 PubMed ↗

Søholm H, Wachtell K, Nielsen SL et al. (2013) Tertiary centres have improved survival compared to other hospitals in the Copenhagen area after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation, 84(2): 162-7.

PMID: 22796541 PubMed ↗

SOS-KANTO 2012 Study Group (2015) Changes in pre- and in-hospital management and outcomes for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest between 2002 and 2012 in Kanto, Japan: the SOS-KANTO 2012 Study. Acute Medicine & Surgery, 2(4): 225-33. [Online]. [Accessed: 5 May 2016]. Available from Article ↗

Stub D, Smith K, Bray JE et al. (2011) Hospital characteristics are associated with patient outcomes following out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Heart, 97(18): 1489-94.

PMID: 21693477 PubMed ↗

Tagami T, Hirata K, Takeshige T et al. (2012) Implementation of the fifth link of the chain of survival concept for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Circulation, 126(5): 589-97.PMID: 22850361 PubMed ↗

Tagami T, Matsui H, Fushimi K et al. (2016) Changes in therapeutic hypothermia and coronary intervention provision and in-hospital mortality of patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a nationwide database study. Crit Care Med, 44(3): 488-95ospital Cardiac Arrest: A Nationwide Database Study. Crit Care Med, 44(3): 488-95.PMID: 26496447 PubMed ↗

van der Wal G, Brinkman S, Bisschops LL et al. (2011) Influence of mild therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest on hospital mortality. Crit Care Med, 39(1): 84-8.

PMID: 20959784 PubMed ↗

Wissenberg M, Lippert FK, Folke F et al. (2013) Association of national initiatives to improve cardiac arrest management with rates of bystander intervention and patient survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA, 310(13): 1377-84.

PMID: 24084923 PubMed ↗