ICU Management & Practice, Volume 21 - Issue 2, 2021

Importance and Objectives

To observe the impact and main contributing factors of stress, anxiety and depression among frontline staff in the intensive care units during the COVID-19 pandemic, and to determine if wellness resources are useful.

Design

Mixed method observational cohort study.

Setting and Participants

All frontline staff working in the intensive care units at one tertiary academic medical centre during the COVID-19 surge.

Main Outcomes and Measures

An online survey consisting of both closed and open-ended questions from validated screening instruments for generalised anxiety and depression was administered. Response rate was 33.5% (67/200), with most respondents being nurses.

Results

A majority of respondents reported excessive worry and difficult to control depressive symptoms. Women and nurses reported more of these symptoms compared with men and non-nurse healthcare workers, respectively. The predominant fears were for personal safety and for loved ones. Participants also reported moral dilemmas about patient care. Wellness resources were not found useful, especially by women and nurses. The qualitative analysis revealed compassion, communication, and empathy to be useful in mitigating the stress and depression from working on the frontlines during the pandemic.

Conclusions and Relevance

The pandemic continues to ravage populations and has a tremendous impact on the mental health of healthcare staff. Greater efforts must be made to listen to the feedback given by these workers to ensure creation and implementation of interventions with the greatest benefit.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic gripped the world at the beginning of 2020, and quickly it was clear that Intensive Care Unit (ICU) staff would bear the brunt of managing thousands of critically ill and dying patients (Wu et al. 2005; CDC 2019). By March 2020, Boston was in the midst of its first surge and our hospital, like others, was dealing with hundreds of patients in all standard ICU locations, as well as in surge ICU locations (non-traditional ICU spaces that were turned into ICUs). These surged ICUs were staffed by physicians, including residents and fellows, nurses, and certified registered nurse anaesthetists (CRNAs) deployed from non-ICU settings (Maves et al. 2020). Even before the pandemic, there were high rates of anxiety, depression, and ethical and moral distress amongst staff in the critical care environment (Mealer et al. 2009). However, since the pandemic began, there has been an increase in reports of significant issues affecting the mental health of healthcare workers (HCWs) on the frontline of this crisis (Azoulay et al. 2020)as the pandemic has led to extraordinary amounts of stress on HCWs (Sasangohar et al. 2020). These stressors, which include increased workload, physical exhaustion, inadequate personal equipment (PPE), risk of nosocomial transmission, and the need to make ethically difficult decisions on the rationing of resources, may have dramatic effects on HCW’s physical and mental well-being (French-O'Carroll et al. 2020) HCWs were also without their usual social supports due to isolation at work and home, which is required for infection control, and the sudden need to work different hours than they used to and in different locations (Epstein et al. 2019). HCWs are, therefore, especially vulnerable to mental health problems, including fear, anxiety, depression and burnout (Rossi et al. 2020). Hospitals and organisations have added a multitude of wellness programmes during the pandemic to provide staff with coping techniques, including online yoga sessions, meditation programmes, stress hotlines and other virtual group activities while maintaining social distancing (Walton et al. 2020).

The objective of this study was to describe the presence of anxiety, depression, ethical and moral distress among ICU HCWs based on job categories during the COVID-19 pandemic surge in our hospital, and to assess the value of wellness programmes offered in mitigating this stress. Our research questions were as follows: to what extent do ICU clinicians report anxiety or depression as a result of working during the pandemic? Do reports of these symptoms vary by gender or profession? How do clinicians describe specific concerns about work, family, or their personal health? Are workplace wellness programmes experienced as helpful in reducing symptoms of anxiety or depression?

Materials and Methods

This study was approved as exempt by our Institutional Review Board (obtained from BIDMC IRB protocol number 2020P000358, version 1). Between the months of March and May 2020, we conducted an online cross-sectional survey including 26 multiple choice and open-ended questions across all ICUs of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, USA. This is a 670-bed academic tertiary care hospital with 77 staffed ICU beds. Two surge ICUs were created to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic at the peak of the surge with 10 patient beds each. The survey link was advertised in all ICUs and weekly reminders were sent to all ICU staff.

We invited physicians, nurses, and respiratory therapists (RTs) as well as CRNAs who were deployed to work in ICUs due to the COVID-19 surge. A fact sheet describing the study was attached to the link for the survey and completion of the questionnaire implied their consent. The survey instrument was developed using validated questions from the generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) screening tool and the depression screening tool developed by the Anxiety and Depression Association of America (Appendix I). In addition, other open-ended questions, created iteratively by the authors following best practices in survey design, asked respondents how they managed fear, anxiety, loss of control and stress (Fowler 2002). Participants were asked to comment on their stress and anxiety levels felt during the pandemic surge at work and at home over two weeks immediately preceding when they took the survey. Additional survey items assessed degree of relief provided by departmental and hospitalwide wellness and stress mitigation programmes. Recognising the time sensitivity of the survey and the possible need for providing support to frontline HCWs, at the end of the survey all resources made available to hospital employees by the wellness committee were added as a link.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were utilised to summarise the data: categorical variables were analysed by frequency count with percentage, and continuous variables were analysed using mean with standard deviation or median with interquartile range, depending on the distribution. Associations were evaluated between measures of anxiety and depression and characteristics such as gender and profession. Differences in ordinal responses created to measure anxiety and depression such as those ranging from “not at all” to “extremely” were assessed with a Mantel-Haenszel Chi-Square test or exact test, as appropriate. Differences in non-ordinal categorical responses were assessed using a Chi-Square or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided p-value < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Qualitative Analysis

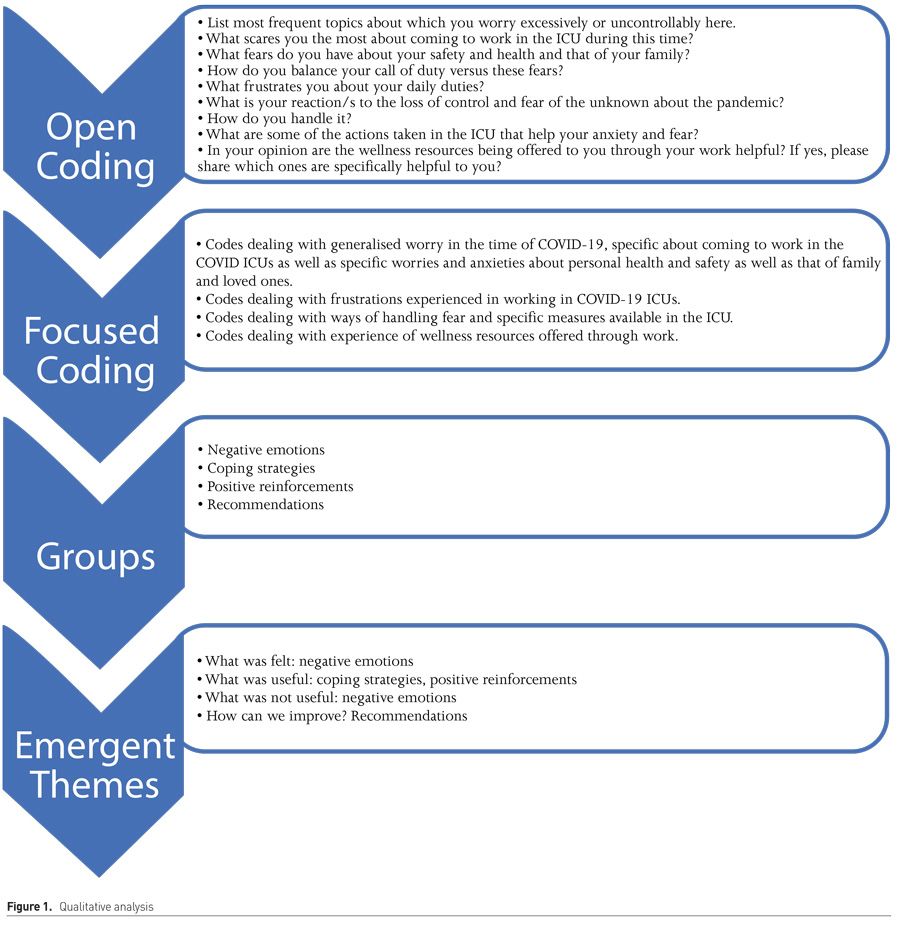

We conducted a content analysis of open-ended survey responses using a constructivist grounded theory approach. The eight open ended questions were initially analysed using open coding with colour highlights depicting various categories. These were then combined into groups using focused coding and subsequently emergent themes were developed from the focused coding categories. These themes were then triangulated with comparison to similar responses within the survey and verified by four separate authors (SS, MH, AL and TS). To ensure trustworthiness, both the quantitative and qualitative results were then discussed with a psychologist for better interpretation and understanding of the findings in light of stress from working on the frontlines during the pandemic. Figure 1 shows the qualitative analysis and coding framework.

Results

Survey Respondents, Setting and Response Rates

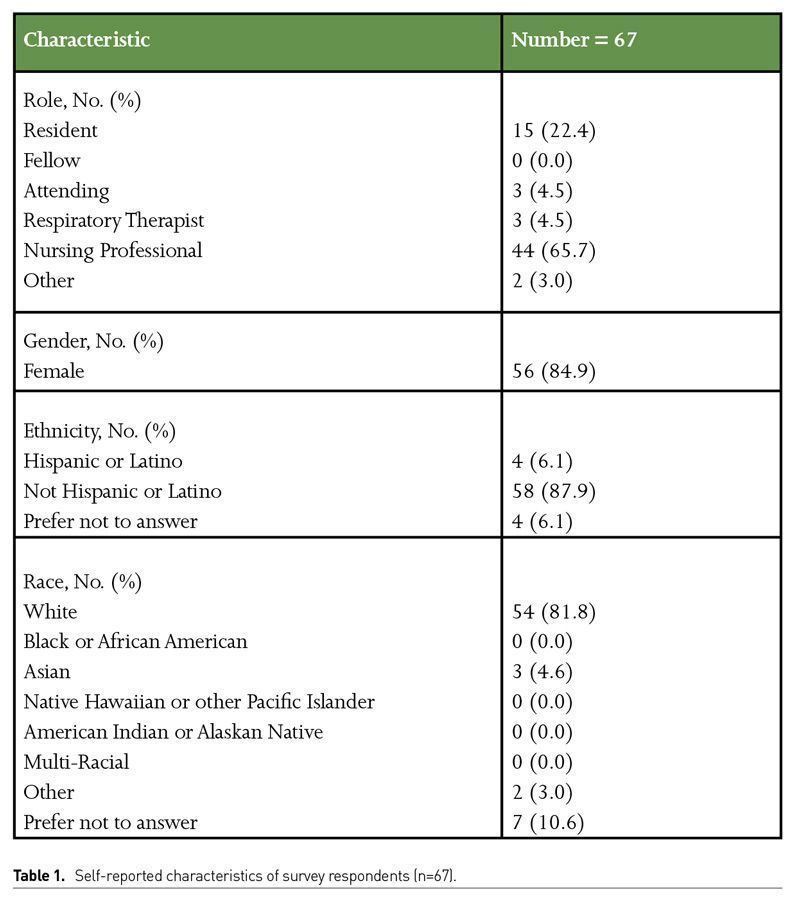

The survey was conducted from March to May 2020, which was during the first surge in Massachusetts. The study was conducted in all medical and surgical ICUs, including the surge ICUs converted from post anaesthetic care units (PACU) in the hospital. Of the 200 frontline ICU staff, including physicians, nurses and respiratory therapists, we received a total of 67 responses for an overall response rate of 34%. All surveys were included in the analysis. Of the respondents, the majority (66%) were nursing professionals, including CRNAs. 27%were physicians, of which the majority were residents (22%) whilst only 5% were respiratory therapists. The normal ratio in ICUs of nurses to physicians to respiratory therapists generally follow this distribution as well. The majority of the respondents were female (85%) and mostly white (88%) (Table 1).

Generalised anxiety screening questions

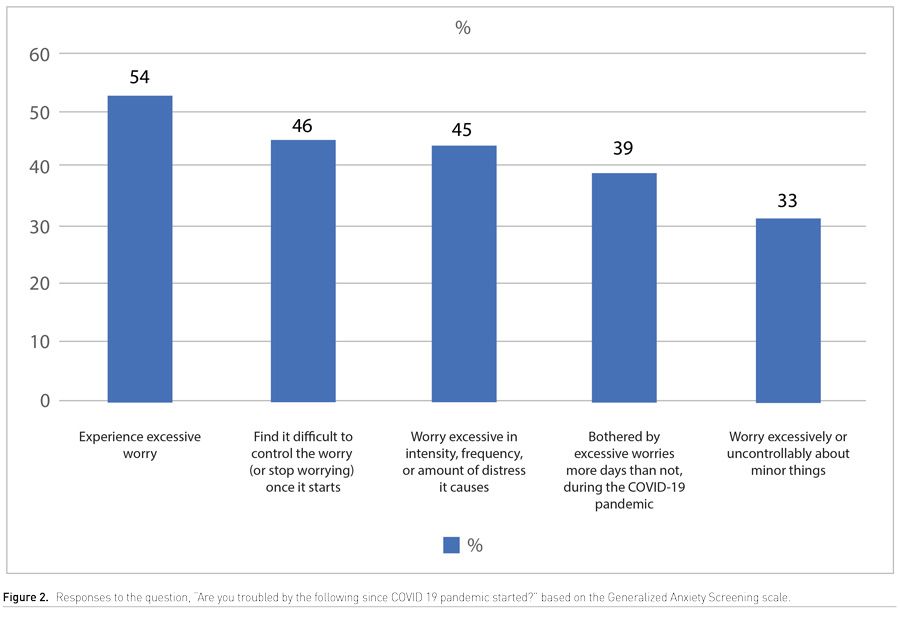

Fifty-four percent of the participants said they felt excessive worry since the start of the pandemic, the symptoms of which included restlessness, irritability, trouble sleeping, easy fatigability, difficulty concentrating and muscle tension (Figure 2). Forty nine percent stated that this worry mildly or did not at all interfere with their life, work, and social and family interactions; 36% stated it moderately interfered, and 15% said that it severely or very severely interfered. When asked how much the excessive worry caused them distress, 44% stated not at all or mildly; 36% said moderately and 20% said severely or very severely.

Depression screening questions

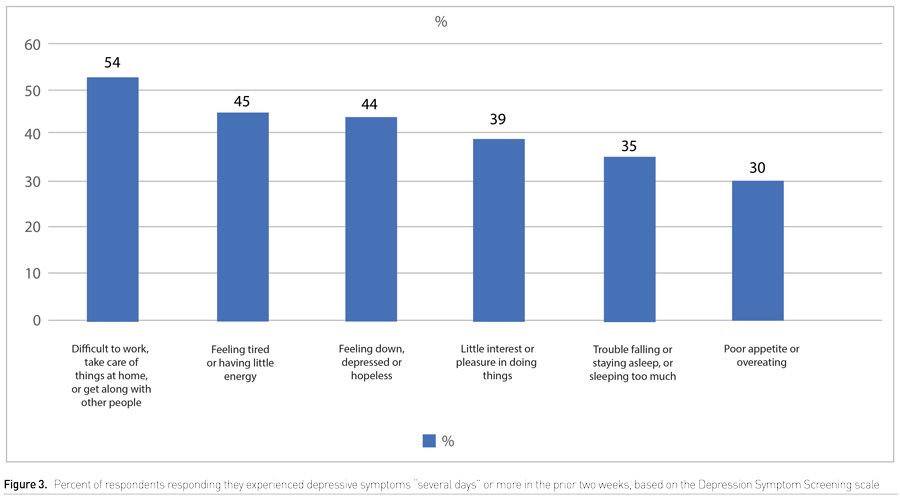

When the participants were asked whether in the past two weeks they have been bothered by any the following problems, the responses were as follows: 39% stated they had little interest or pleasure in doing things for several days, 44% said they were feeling down, depressed or hopeless for several days; 35% felt they had trouble sleeping for several days; 41% stated they were feeling tired or having little energy over several days; 31% were either overeating or had poor appetite over several days. However, when asked ‘how difficult have the problems you experienced made it for you to do your work, take care of things at home, or get along with other people?’ 55% stated ‘somewhat difficult’ and 15% stated 'very or extremely difficult’ (Supplemental Digital Content Figure 3).

Participant reports of helpfulness of hospital wellness resources

A specific question was asked whether the participant found the wellness resources being offered to them through their work helpful, and if so, which ones. Seventy percent of the respondents reported that these resources were not helpful.

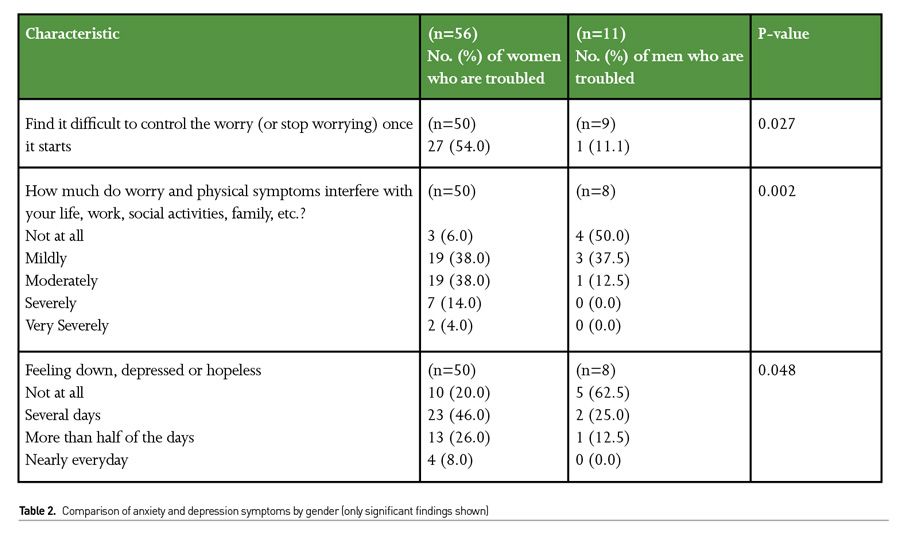

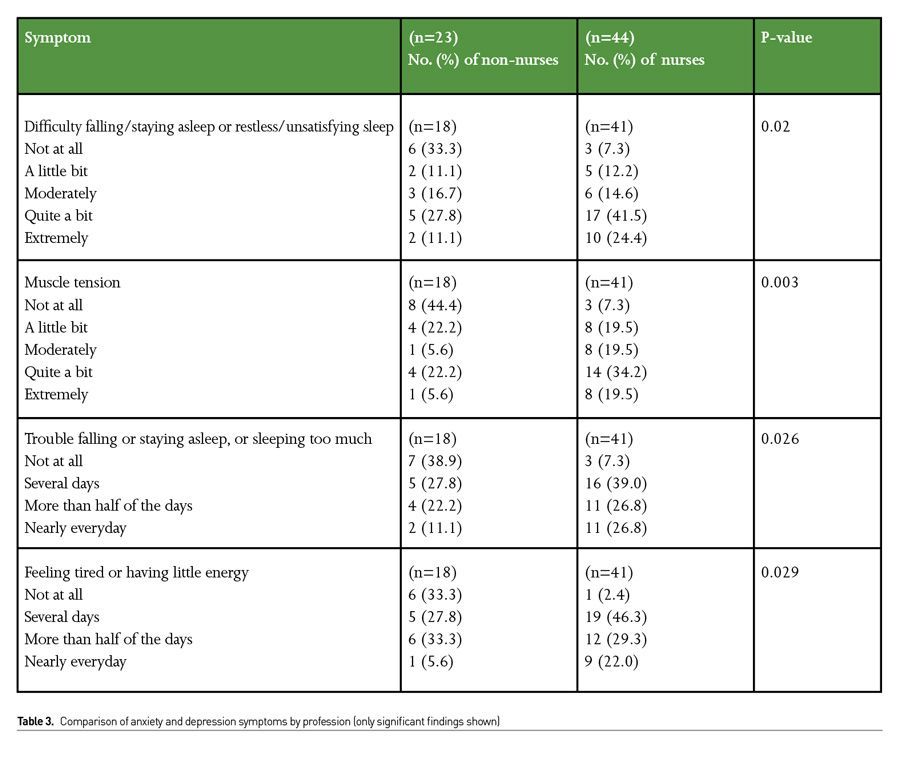

Analysis of associations of findings with gender and profession

When feelings of worry were compared by gender, women were more likely than men to report that it was difficult to control this worry once it started (54% versus 11.1%, respectively, p=0.027). Also, women were more likely to report that worry and physical symptoms interfered with their life, work social activities and family life as compared to men (56% of women felt this “moderately” to “very severely” versus 13% for men, p=0.002). Similarly, there is a significant difference in the number of depressive symptoms felt over several days by males and females, as 46% of women felt down, depressed or hopeless for several days, vs 25% of men (p=0.048) (Table 2).Women and nurses felt that wellness resources offered through work were not helpful, although this was statistically not significant. (p=0.059) (Table 3).

Qualitative Analysis Results

Emergent Themes as illustrated in Figure 1:

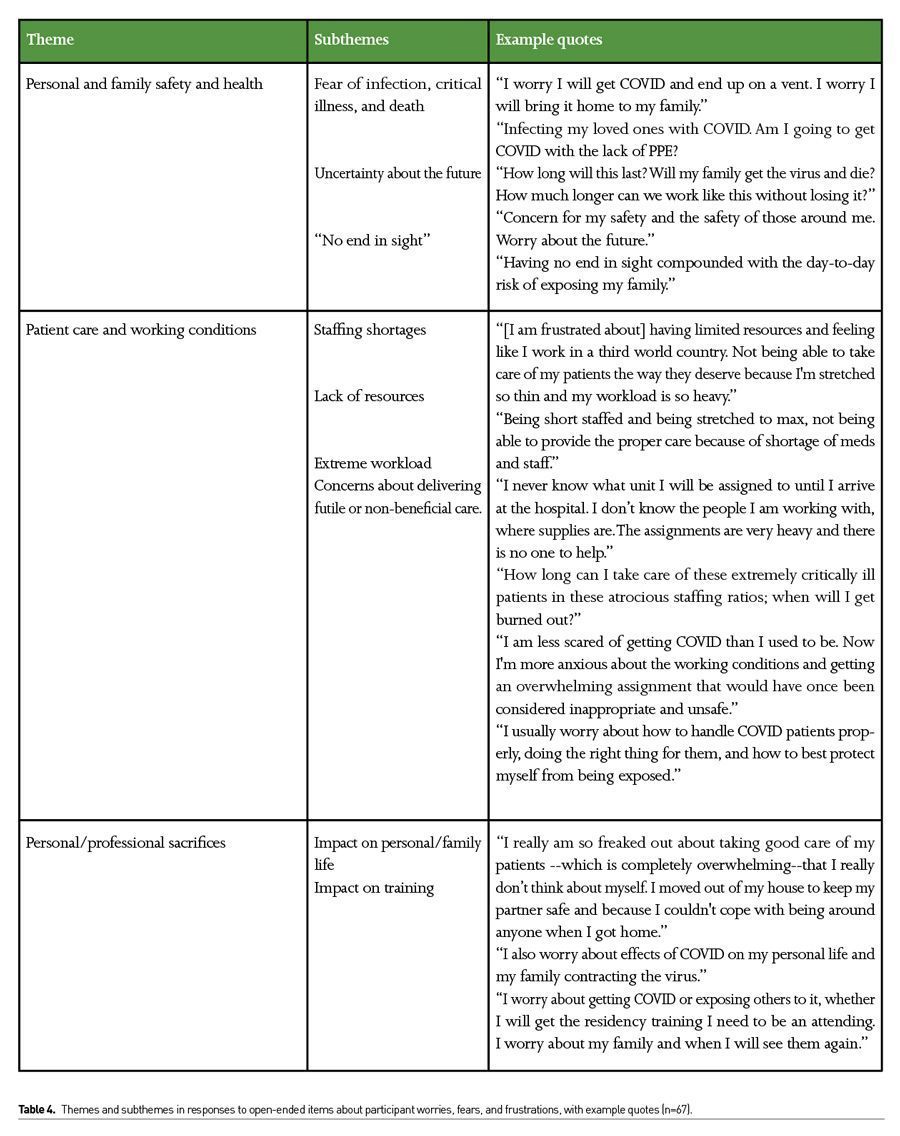

1. What was felt

Respondents reported worries and fears about their own safety, that of their families, and concerns about being able to adequately care for their patients, and these themes were frequently intertwined (Table 4). Themes included dealing with generalised worry in the time of COVID-19, specifically about coming to work in the COVID-19 ICUs, as well as specific worries and anxieties about personal health and safety as well as that of family and loved ones, including the prospect of death or being on a ventilator. Participants described specific safety concerns, especially in the surge ICUs which were open units with multiple COVID-19 patients. Many participants expressed personal concerns about burnout, particularly given the level of uncertainty about the future with an illness that had “no end in sight.”

Respondents expressed deep concerns about the ability to provide adequate patient care. A major concern was a lack of staff to care for more than one critically ill patient who required a high level of support. Many of the nurses were deployed from post anaesthesia care units and new to ICU protocols. Others voiced concerns of delivering futile or non-beneficial care. One described it as “fear of harming patients by doing things to them that ultimately will not help.” Many respondents reported feelings of impotence with regard to improving patient outcomes. More than 50% of the nurses redeployed to the ICU from medical or surgical floors described this feeling of being inadequate.

One participant described the “nightmares” and “constant worry” related to her concerns for her patients, and how this could easily happen to her own family.They also frequently noted concerns about lack of resources in staffing and PPE, as well as numerous personal and professional sacrifices.

Staff also described the potential personal and professional sacrifices they experienced, or anticipated experiencing, due to the pandemic. This included impacts on life events, such as upcoming weddings, and fears about impacts on training among residents.

2. What was useful

Themes dealing with ways of handling fear and specific measures available in the ICU

Some of the emotions reported were fear, anger, sadness, yet there was a display of teamwork, support and compassion which improved the morale of the HCWs, and increased job satisfaction. This embodiment of friendship, camaraderie, and support can be seen in this statement: “Sharing with other colleagues about them when we have the time. Teamwork: knowing that we have each other’s backs and are helping each other get through every shift. Having the extra help of redeployed "med-surg" nurses has been great. The intensivist staff has been amazing in assisting with and helping guide our care.” Another said, “Patients come first, and we need to get the job done. My fellow nurse friends build each other up!”

3. What was not useful

Themes dealing with experience of wellness resources offered through work

These were not used widely or considered useful. However, positive reinforcements such as town halls, reassurances, compassionate peer support and empathy helped a lot. One respondent mentioned the song played when COVID-19 patients were extubated, “I feel good when the ‘Sweet Caroline’ plays over the hospital speakers. It makes all the work and stress worth it that some patients are making it home.” When asked what was helpful, one said “a manager that communicates with their staff.”

4. How can we improve?

Respondents suggested better teamwork as they found the peer support helpful, as well as communication with managers and leadership. One participant stated, “being with my co-workers as we are all in this together” as a benefit. Another said, “Just seeing how my boss goes about her business is very inspiring. Also, the entire team. It motivates. Therefore, I have no time for anxiety or fear.”

Discussion

This study explored the feelings of stress and depression experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic by frontline staff including physicians, nurses and respiratory therapists in the ICU. Of the 200 staff members deployed to these ICUs during the pandemic from March to May 2020 in one tertiary care hospital, 34% responded to an anonymous online survey. The mixed methods methodology provided another dimension to understand the quantitative as well as qualitative responses on stress, worry and depression (Sharour et al. 2019).

The results suggest that women and nurses were especially susceptible to worry, depression, and feelings of despair on the frontlines as compared to other professionals. They also felt that the wellness resources offered to them through work were not helpful. The worry felt by the survey participants during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic was about personal health and safety as well as that of their family and loved ones. The areas that were uncovered from the qualitative data also focused on personal safety and health, including burnout and mental fatigue, as well as concern for others. Participants felt worried about working outside their scope of training or experience. Another area of anxiety was staff and PPE shortage, as well as personal finances and career prospects due to disrupted training. There was evidence of work-related pressure and feelings of guilt about sacrificing personal responsibilities and those towards their families. They feared dying alone as they agonised over their patients dying without loved ones near.

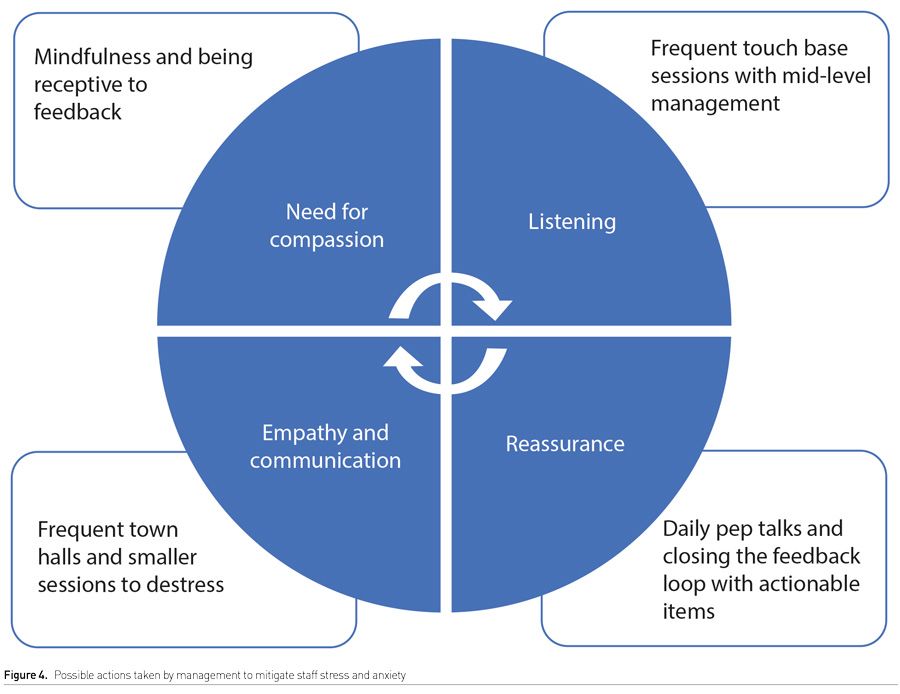

When asked to discuss frustrations experienced whilst working in COVID-19 ICUs, respondents expressed moral dilemma and stress about delivering futile care at times when the prognosis of their patient was dire, anxiety about personal skills when faced with extremely sick patients, especially as some staff were redeployed from inpatient, non-ICU floors. They also feared limited resources, stretched staff, changing policies and uncertainty of the future. This was especially voiced when surge ICUs were announced, resourced and staffed within days due to rapid changes in the work environment and local peer support systems. The discomfort of wearing PPE for long hours and the heavy workload experienced was also a source of burnout. Most respondents, especially women and nurses, did not find any of the wellness resources such as yoga classes, meditation websites and online courses useful. Their main worries were not addressed by this information and offerings. What participants found immensely useful was the peer support, compassion and camaraderie felt whilst working on the frontlines and when empathetic communication was offered by managers and leadership, in the shape of town halls or meetings. This was echoed by all professionals on the frontlines.

Supplemental Digital Content Figure 4 depicts some of the possible ways in which such compassionate support can be offered to ICU frontline staff. These include daily sessions to listen to the staff and hear them out, being sensitive and mindful to their feelings and emotions, compassionate communication with trained leaders and to complete the feedback loop with giving explanations on actionable points raised. This will establish trust and build an empathetic and meaningful relationship which allows staff to work with a clear message that they are cared for and their genuine worries are heard.

Limitations

Our study had several of the limitations that come inherently with survey research. One general limitation is the oversimplification of what is the reality being experienced (Jick 1983). The arbitrary design of questionnaires and multiple-choice questions with pre-conceived categories represents a biased and overly simple view of reality and capturing only a single moment rather than a period of time. However, we attempted to overcome some of this bias by using validated anxiety and depression screening questionnaires. Also, the use of qualitative methods in addition to the quantitative survey and use of triangulation attempts to reduce the weaknesses and limitations of the cross-sectional surveys (Cook and Reichardt 1979). Our response rate was roughly the average rate surveys may yield. This is a combination of the ‘survey fatigue’ experienced in medicine, and the extremely busy schedules of the cohort being surveyed during the pandemic.

Conclusion

The first surge of the pandemic drained frontline workers in the ICU (Schwartz et al. 2020) They experienced anxiety, depression and stress. Numerous studies from across the world have revealed similar results (Cai et al. 2020; Hofmeyer et al. 2020). Health-care providers showed their resilience and the spirit of professional duty to overcome these difficulties (Adams and Walls 2020). Leaders need the knowledge, skills and behaviours to create and sustain cultures of compassion and kindness. Comprehensive support should be provided to safeguard the wellbeing of these healthcare providers. Our study shows that compassion and regular and reassuring communication with leaders and peers prove more useful than wellness resources in mitigating the stress of working in the pandemic and motivating the staff. This communication is vital to promote preparedness and efficacy in crisis management.

Acknowledgement

We wish to acknowledge the valuable contributions of: Smith, Joshua, MD, PhD (psychology), Lauren, Kelly, MS (statistics), and Dwyer, Julia (administrative support).

Conflict of Interest

None.

Appendix I

References:

Adams JG, Walls RM (2020) Supporting the Health Care Workforce During the COVID-19 Global Epidemic. JAMA, 323(15):1439–1440. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.3972

Azoulay E, De Waele J, Ferrer R et al. (2020) Symptoms of burnout in intensive care unit specialists facing the COVID-19 outbreak. Ann Intensive Care, 10(1):110. doi:10.1186/s13613-020-00722-3

Cai H, Tu B, Ma J et al. (2020) Psychological impact and coping strategies of frontline medical staff in Hunan between January and March 2020 during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Hubei, China. Med Sci Monit., 26:e924171.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim infection prevention and control recommendations for patients with confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) or persons under investigation for COVID-19 in healthcare settings. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/infection-control/control-recommendations.html

Cook TD, Reichardt CS, eds. (1979) Qualitative and quantitative methods in evaluation research. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Epstein EG, Whitehead PB, Prompahakul C et al. (2019) Enhancing understanding of moral distress: the measure of moral distress for health care professionals. AJOB EmpirBioeth., 10:113–124.

Fowler FJ (2002) Survey Research Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

French-O'Carroll R, Feeley T, Tan MH et al. (2020) Psychological impact of COVID-19 on staff working in paediatric and adult critical care. Br J Anaesth., S0007-0912(20)30824-2. doi:10.1016/j.bja.2020.09.040

Hofmeyer A, Taylor R, Kennedy K (2020) Fostering compassion and reducing burnout: How can health system leaders respond in the Covid-19 pandemic and beyond?. Nurse Educ Today. 94:104502. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104502

Jick TD (1983) Mixing qualitative and quantitative methods: triangulation in action. In: Van Maanen J, ed. Qualitative Methodology. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Pub. 117-134.

Maves RC, Downar J, Dichter JR et al. (2020) Triage of Scarce Critical Care Resources in COVID-19 An Implementation Guide for Regional Allocation: An Expert Panel Report of the Task Force for Mass Critical Care and the American College of Chest Physicians. Chest, 158(1):212-225. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.063

Mealer M, Burnham EL, Goode CJ et al. (2009) The prevalence and impact of post traumatic stress disorder and burnout syndrome in nurses. Depress Anxiety, 26(12):1118-1126. doi:10.1002/da.20631

Rossi R, Socci V, Pacitti F (2020) Mental health outcomes among frontline and second-line health care workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Italy. JAMA.

Sasangohar F, Jones SL, Masud FN et al. (2020) Provider burnout and fatigue during the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons learned from a high-volume intensive care unit. AnesthAnalg. doi: 10.1213/ane.0000000000004866.

Schwartz R, Sinskey JL, Anand U, Margolis RD (2020) Addressing Postpandemic Clinician Mental Health : A Narrative Review and Conceptual Framework Ann Intern Med.,M20-4199. doi:10.7326/M20-4199

Sharour LA, Omari OA, Malak MZ et al. (2019) Using Mixed-Methods Research to Study Coping Strategies among Colorectal Cancer Patients. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs., 7(1):81-87. doi:10.4103/apjon.apjon_20_19

Walton M, Murray E, Christian MD (2020) Mental health care for medical staff and affiliated healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care, 9(3):241-247. doi:10.1177/2048872620922795

Wu KK, Chan SK, Ma TM (2005) Posttraumatic stress after SARS. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 11:1297–1300. 10.3201/eid1108.041083