ICU Management & Practice, Volume 21 - Issue 2, 2021

Introduction

When COVID-19 emerged as a new pathogen, the pictures and stories of the devastation it was bringing focused attention on the mental health of acute care workers, and, in the media, on ICU teams in particular (Du et al. 2020; Lai et al. 2019; Preti et al. 2020; Rossi et al. 2020). The focus highlighted the understanding of the key role these teams would have to play in the global response to save as many lives as possible -- in the face of increasingly exhausted resources and what appeared to be increasingly incredible odds. The media attention to the issues of mental health, burnout and resilience in the ICU, opened the door to discussions of the psychological and emotional impacts of struggling to deal with fear, struggling to save the lives of so many while being powerless to save the lives of so many others, and bearing witness to tremendous loss and grief. In the face of an emerging pathogen, healthcare workers experienced normal human reactions - dread in anticipation of what was to come, anxiety, distress, fear of becoming ill, even possibly dying or even worse bringing the virus home to their families (Du et al. 2020; Lai et al. 2019; Preti et al. 2020; Rossi et al. 2020). The first wave of COVID-19 saw outpourings of public support for the “heroes” on the frontlines which, while intended to show appreciation for healthcare workers, for many, added to their own psychological distress especially in the face of such a large number of patient deaths (Nielsen 2020). That was then, in March 2020. Where are we now one year later? What have we learned and what can we do to cope going forward?

After a year of this pandemic, this article will explore what we currently understand about the psychological impacts experienced by ICU teams and provide practical guidance to help build personal and team resilience as the journey with COVID-19 continues with no end in sight.

Mental Health Impacts of the Pandemic on ICU Teams: What Do We Know?

For ICU professionals around the world, the pandemic has caused significant psychological distress. Rates of anxiety range between 46-67%, depression 30-57%, symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder 32-54% and burnout 51% (Azoulay et al. 2020a; Azoulay et al. 2020b; Crowe et al. 2020). One study reported 6.3% rates of severe depression, 39.5% PTSD, 11.3% severe anxiety and 7.2% problem drinking with 13.4% of respondents reporting frequent thoughts of self-harm or suicide in the past two weeks (Greenberg et al. 2020)). These levels of distress are similar to those seen in previous outbreak situations such as SARS and MERS (Khalid et al. 2016; Styra et al. 2003). As also seen across non-ICU studies, female gender and nurse-professional status were consistently associated with higher levels of psychological distress (Azoulay et al 2020a; Azoulay et al. 2020b; Crowe et al. 2020).

Currently, identified causes of psychological distress include: fears of being infected, anxiety related to rapidly changing policies and information, the need to balance patient care and personal safety, managing commitments to self and family, inability to rest, struggling with difficult emotions, difficulty in communicating and providing support to families due to the impact of restrictions in visitation policies, and finally failing to provide adequate support at the end of life and witnessing hasty end-of-life decisions (Azoulay et al. 2020a; Crowe et al. 2020).

Interestingly, increased symptoms of depression and burnout have been reported based on clinicians’ ratings of the ethical climate in which they are working where ethical climate was defined as “individual perceptions of the organisation that influences attitudes and behaviour and serves as a reference for employee behaviour" (Azoulay et al. 2020b). Research prior to the pandemic revealed associations between perceptions of staffing and fair treatment in the workplace and physician and nurse burnout and identified the need for these factors to be systematically addressed (Rubin et al. 2021). Unfortunately, the very nature of a pandemic will tax staffing to its limits and likely exacerbate pre-existing perceptions of unfair treatment. Others have described the importance of healthcare organisations taking steps to hear, protect, prepare, support and care for their healthcare teams to decrease staff anxiety and their ability to cope (Shanafelt et al. 2020). Such efforts include access to PPE, prevention of infection and exposing their families to risk, access to rapid testing, care for themselves or their families should they become infected, access to childcare and support for basic personal needs (e.g., food, hydration, lodging, transportation) that reflects increased work hours, school closures, and voluntary redeployment, educational support if re-deployed and access to up to date information and communication (Shanafelt et al. 2020).

An Issue of Needs

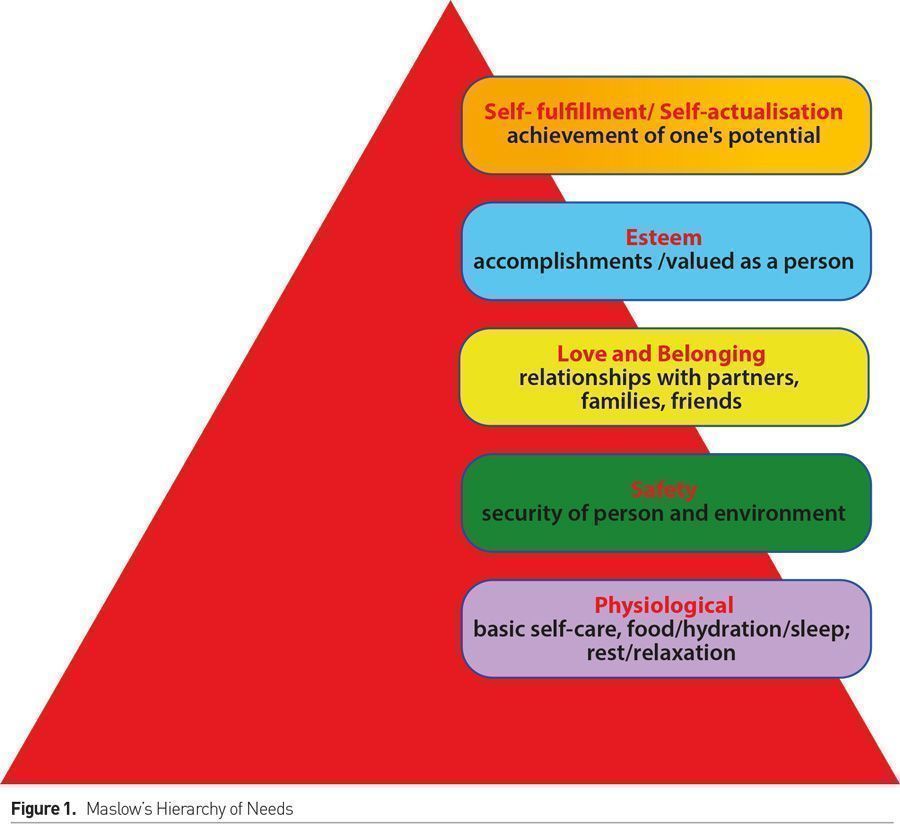

Abraham Maslow’s foundational work in human psychology proposed that humans are motivated by five categories of value-based needs: physiological, safety, love and belonging, esteem and self-actualisation (Maslow 1954). These needs are described as a hierarchy with more basic needs, the ones that are most crucial for any individual to have met, located in the bottom tier and higher-level needs at the top. Maslow’s theory proposes that higher level needs, those that make us feel fulfilled as individuals or, in the workplace, as professionals, cannot be achieved unless our more basic needs are met. His theory suggests that psychological harms can, or will, ensue if basic needs - physiological, safety, love and belonging, esteem - are not met. Self-actualisation needs are linked to perceived degree of happiness (Maslow 1954; Lester et al. 1983); however if unmet, they will not lead to psychological harm. Maslow’s needs are commonly represented as a pyramid (Figure 1).

Maslow’s Needs and the ICU Professional: Where Do We Go From Here?

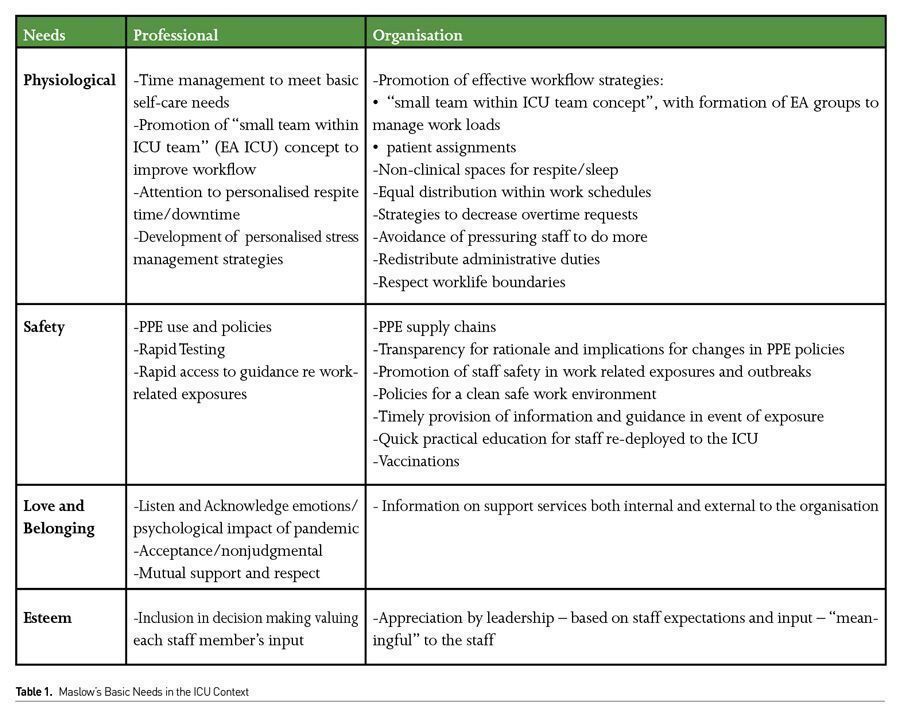

In Maslow’s framing of needs, it becomes apparent that much of the research in the ICU on how to mitigate the psychological impact of the pandemic engage the bottom tier of needs in this pyramid and engage hospitals, ICU management and ICU professionals (Table 1).

Physiological needs for the ICU healthcare professional require a daily organised planning of patient care workflow (as much as possible) with patient assignments planned to allow time for personal basic self-care. ICU healthcare professionals (RNs, allied health and physicians) should consider creating small intra-ICU team groupings - Equitable Activity ICU (EA ICU) teams- to assist one another with workloads. Workload management principles should be applied to ensure that there is a process of efficiently distributing and managing work across ICU teams. The need for self-respite only increases in a pandemic situation and creative approaches (time and/or workflow based) are required to provide brief periods for people to regroup during their working hours. ICU nurses are farther ahead than most ICU physician groups in recognising the importance of such workflow structures and physicians should explore ways of changing their workflow similarly.

Quality ICU management means meeting a responsibility to promote time for self-care and respite as part of a healthy work environment and to provide sufficient, safe, comfortable respite places (Gordon et al. 2020). These places would ideally be less clinical in nature, allow ICU professionals to have a change in headspace/change of scene, to eat meals, hydrate and even sleep. The importance of the provision of such places when working long hours in PPE cannot be overstated. ICU leadership needs to acknowledge and meet responsibilities to ensure call and work schedules are equally distributed to promote rest and sleep and to provide on call spaces for staff who need to stay overnight, if these do not already exist. Within the ICU team some professionals, due to their roles and responsibilities, are asked to shoulder more work than others and this should be recognised and attention paid to ways to assist them in order not to overwhelm any individual professional. Finally hospital/ICU management need to define clear boundaries as to what constitutes an urgent issue to decrease workloads during off hours and ensure rest and respite e.g.. non-urgent issues and emails should be dealt with during weekday work hours only.

In many ICUs as the pandemic continues, the struggle with staff retention is becoming an increasing challenge, placing a growing burden on those remaining and increasing requests on behalf of ICU management and hospitals to work more overtime and/or re-deployed. There is a need for ICU management teams to monitor and develop strategies to decrease overtime shifts for staff and avoid the application of pressure, with or without financial incentives, to ask any professional to do more than they can (i.e. accept that no means no - without shame). While re-deployed nurses and physicians can help offset workloads, the use of redeployed staff may lead to anxiety and stress if the ICU team has no understanding of their knowledge and skill level: rather then knowing how to work with them, the ICU teams must first figure out responsibilities with which they may be entrusted. The presence of EA groups would provide greater support not only to the deployed staff but also help ensure that adequate support is available to them no matter how busy their own team might be. The development of a quick task-based-training resource for re-deployed colleagues would at least provide the ICU team with confidence in the existence of a common baseline of those they are now supervising.

From a safety needs perspective, now that we are over a year into the pandemic, most ICUs in high income countries have addressed issues of workspaces and appropriate PPE to keep team members safe. Stable supplies are generally available, though concern still exists that should the pandemic worsen, issues of supply may once again become problematic. A need for transparency remains on the part of ICU and hospital management regarding decision-making and policies around changes in PPE to maintain trust and a sense of security in the workplace. Now, rapid testing for ICU teams members and their families is generally readily available as is access to appropriate information and care in the event of infection. With the vaccine roll out, most countries have already, or have made significant inroads, into vaccinating ICU professionals. In low and middle income countries (LMICs) though, supply chains of PPE are vulnerable at the best of times and face ongoing challenges placing safety needs of all healthcare workers at risk.

Moving forward, as variants cause recurrent waves, hospital and/or ICU exposures are new and ongoing sources of psychological distress that have not yet been discussed in existing literature. When an exposure is identified, Infection Prevention and Control (IPAC) team members typically place the patient on isolation. Yet information on implications for staff and precautions, if any, they need to take are not consistently nor clearly communicated. Both ICU and hospital management need to recognise that such a lack of transparency and difference in treatment of patients and staff may lead to ICU staff psychological distress, and perceptions of staff feeling less valued and less protected at times when they may actually be at higher risk. Moreover, depending on the source of exposure, recognition is needed that the ICU team can play an invaluable role in identifying both other staff at risk and specific environments that need decontamination. Such an approach will prevent outbreaks by ensuring everyone is diligent about wearing their PPE and cleaning their work environment. Understanding the level of personal risk helps reduce fear and anxiety and possible post-traumatic stress symptoms. Misguided attempts, in the name of privacy, to not be forthcoming with timely instructions to staff, results in mistrust. The psychological impacts may then compromise staff retention. Both privacy and confidentiality standards can be met while providing key information to meet the safety needs of the ICU team.

A sense of community and belonging can be achieved if a tightly knit team is created where everyone is valued, fostered and respected. As research has revealed, the mental health impacts of a pandemic are different for different team members. Moreover professionals may experience the impacts of the pandemic differently at different moments in time. They may be able to cope better some days as compared to others. These differences are normal. The focus on mental health in the pandemic ICU should be that it is acceptable to have more open discussions of how we are feeling as ICU professionals, to share what we do to cope and what helped us get through the bad times. Critical care has traditionally been a field in which the emotional and psychological impacts of what is seen when caring for people with life-threatening illnesses are compartmentalised at work and processed in private, if they are processed at all. This risks open discussions of psychological/emotional impact being perceived as weakness or an inability to cope with the work. In a pandemic, private time for processing may not exist and breaking down thoughts and emotions may be so delayed that it risks the ability to perform professional roles. We need to listen to and acknowledge how we and our colleagues are feeling without rushing in trying to fix them which can be misperceived as diminishing their experiences or shutting down discussions. As a field, we are very skilled at providing support to families; its more than time we do the same for each other. There should never be any hesitancy in asking for help. ICU management and hospitals should provide clear information on where to turn for help whether internally or externally for those not comfortable seeking help from their place of work.

Esteem needs can be met quite simply by ICU and hospital management recognising the hard work, sacrifices and efforts made by each ICU professional during this pandemic in a meaningful way i.e. recognising the person in the professional and saying thank you. Particular attention to recognising staff efforts during more challenging times may help reduce stress and burnout. It is important to pay attention to the fact that pandemics can often result in new hierarchical structures which can promote siloing and discontent, rather than collaboration. Changes in organisational structure at this time should be undertaken cautiously in order not to alienate already pre-existing working teams.

Finally, self-actualisation needs can best be met by acknowledging and valuing the creativity ICU professionals can bring to critical care during such times and maximising its effectiveness in achieving our common goal of saving as many lives as we can.

Recognition of the Person in the Professional

The most obvious problem with Maslow’s needs and our discussion of how these can be met in the professional context is that members of the ICU team are not only professionals, they are people. It is the person and not only the professional who experiences these mental health impacts. It is the whole person, not only the professional whose needs must be met in order for them both to survive this pandemic as intact from a mental health perspective as possible. Meeting the basic needs in the professional context will help decrease the very human fears of bringing infection home to those we love. Yet it is not only bringing infection home that needs to be feared, it is bringing home the mental health impacts of living through the pandemic ICU, of having the most important people in our own lives see the psychological and emotional costs of the terrible moments lived, and our anxiety, depression and distress over those yet to come. In other words, it is our need for love and belonging as a person that is most at risk. Watching the professional re-become the whole person, watching them unpack all that has been compartmentalised, being unsure, or not knowing how to help, and witnessing the rebuild into the professional once more before the return to work is traumatising to those we love and who love us (Busa 2021). Yet where and how do you find the balance between love, belonging and sharing, all of which are vital in any relationship and inadvertently asking your loved ones to assume the role of counsellor? No research exists exploring what people in our lives would find helpful from us not to feel excluded from a significant part of who we are. Nor is there research to help us understand how to communicate when we are okay, when we are not and what would help us cope along our shared journey. Now is the time for it to start. It is hard enough to manage this critical aspect of our lives in normal times and the challenge has now grown exponentially for so many of us. The loss of personal love and belonging is an extraordinarily high price to pay and frankly professional belonging, esteem and self-fulfillment needs, if achieved, are rarely enough to compensate. In view of the known psychological effects on professionals, loss of love and belonging on a personal level, would be expected to result in an exponential rise in distress and burnout. More research is needed and yet any psychological support provided by ICU and hospital management, to be successful, needs to focus on the personal and not only the professional.

Conclusion

The psychological impact of what we have lived through in the past year in the ICU can’t be managed in the same way as that of the past; the experiences are too overwhelming. Attention to the mental health of ICU team members as professionals and individuals, having resources, open dialogues about meeting basic needs, how we are feeling, what we are doing to cope are both needed and welcome. By meeting the fundamental needs of the person in the professional, we can reduce the psychological impact of this and future pandemics.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References:

Azoulay E, Cariou A, Bruneel F et al. for the FAMIREA Study Group (2020a), Symptoms of Anxiety, Depression, and Peritraumatic Dissociation in Critical Care Clinicians Managing Patients with COVID-19. A Cross-Sectional Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med., 22(10):1388–1398.

Azoulay E, De Waele J, Ferrer R et al. on behalf of ESICM (2020b) Symptoms of burnout in intensive care unit specialists facing the COVID-19 outbreak. Annals of Intensive Care, 10:110

Busa S (2021) The emotional toll of living with a health care worker in the pandemic. Vox. Available from vox.com/first-person/22323247/covid-coronavirus-pandemic-healthcare-frontlines-essential-workers-spouse-partners,

Crowe S, Fuchsia A, Brandi H et al. (2021) The effect of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of Canadian critical care nurses providing patient care during the early phase pandemic: A mixed method study. Intensive & Critical Care Nursing. doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2020.102999

Du J, Dong L, Wang T et al. (2020) Psychological symptoms among frontline healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan. Gen Hosp Psychiatry, 67:144-5.

Gordon H, Styra R, Bloomberg N (2020) Staff Respite Units for Healthcare Providers during COVID-19. Jour Concurrent Disord., 2(3):24-39.

Greenberg N, Weston D, Hall C et al. (2020), The mental health of staff working in intensive care during COVID-19. MedRxiv. Available from medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.11.03.20208322v2

Khalid I, Khalid TJ, Qabajah MR et al. (2016) Healthcare Workers Emotions, Perceived Stressors and Coping Strategies During a MERS-CoV Outbreak. Clin Med Res., 14:7-14. doi:10.3121/ cmr.2016.1303

Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y et al. (2020) Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3(3)e20397.

Lester D., Hvezda J. Sullivan S et al. (1983) Maslow Hierarchy of Needs and Psychological Health. J Gen Psychology, 109:83-85

Maslow AH (1954) Motivation and Personality. New York Harper and Row

Nielsen N (2020), The view from the ICU. Stanford Magazine. Available from stanfordmag.org/contents/the-view-from-the-icu-covid19.

Preti E, Di Mattei V, Perego G et al. (2020) The Psychological Impact of Epidemic and Pandemic Outbreaks on Healthcare Workers: Rapid Review of the Evidence. Curr Psychiatry Rep., 22:43. doi: 10.1007/s11920-020-01166-z.

Rossi R, Socci V, Pacitti F et al. (2020) Mental Health Outcomes Among Frontline and Second-Line Health Care Workers During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic in Italy. JAMA Netw Open, 3(5):e2010185. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10185.

Rubin B, Goldfarb R, Satele D et al. (2021) Burnout and distress among physicians in a cardiovascular centre of a quaternary hospital network: a cross-sectional survey. CMAJ Open. doi:10.9778/cmajo.20200057

Shanafelt T, Ripp J., Trockel M (2020) Understanding and Addressing Sources of Anxiety Among Health Care Professionals During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.5893

Styra R, Hawryluck L, Robinson S et al. (2008) Impact on health care workers employed in high-risk areas during the Toronto SARS outbreak. J Psych Res., 64:177-183.