Monitoring nutrition in the ICU is significantly different from monitoring other activities. For example, if we look at haemodynamics, it is pretty easy. We can monitor blood pressure, cardiac output etc. We can deliver a drug and look at its effect to see if it works or not, and, if it doesn’t, we can simply change the drug. These are simple activities that we do in the ICU every day.

But is the same true for nutrition? It is possible to monitor the compound we deliver, but how do we monitor the effect? How do we determine the effect of enteral nutrition, for example? How do we measure that? How do we see the side effects? Even if we observe intolerance to enteral nutrition, can we say for sure why that is so? Maybe it’s because of the patient’s disease itself or some other reason. The point is that if we cannot measure what we actually do, how can we know what products we should administer?

Large scale, pragmatic trials are needed to better understand this. A study, yet unpublished, was conducted with 220 patients in our 39 bed mixed surgical medical ICU. There is a nutrition protocol in place, and the assumption is that nutrition is monitored adequately. But findings from this study will clearly demonstrate that this is not the case.

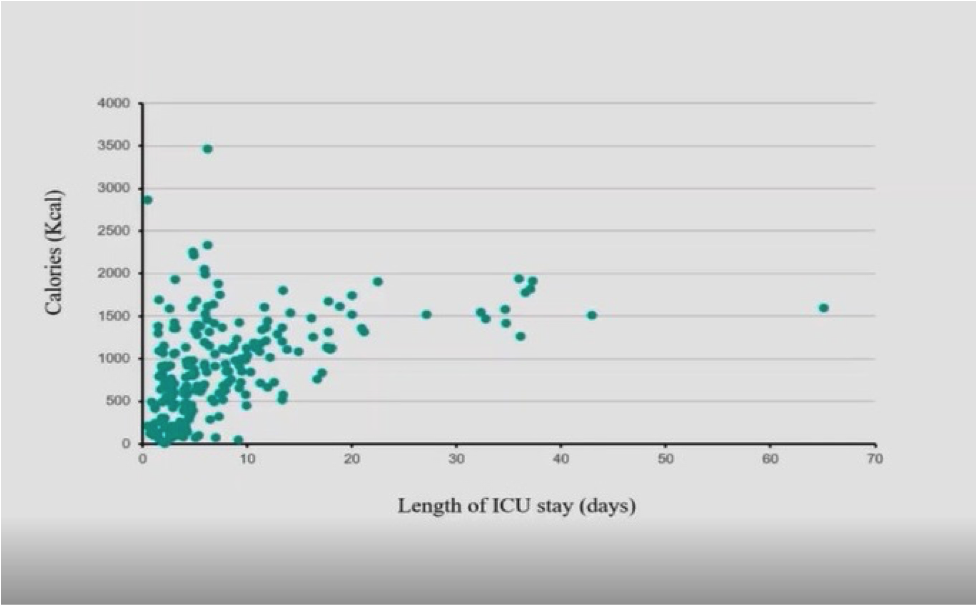

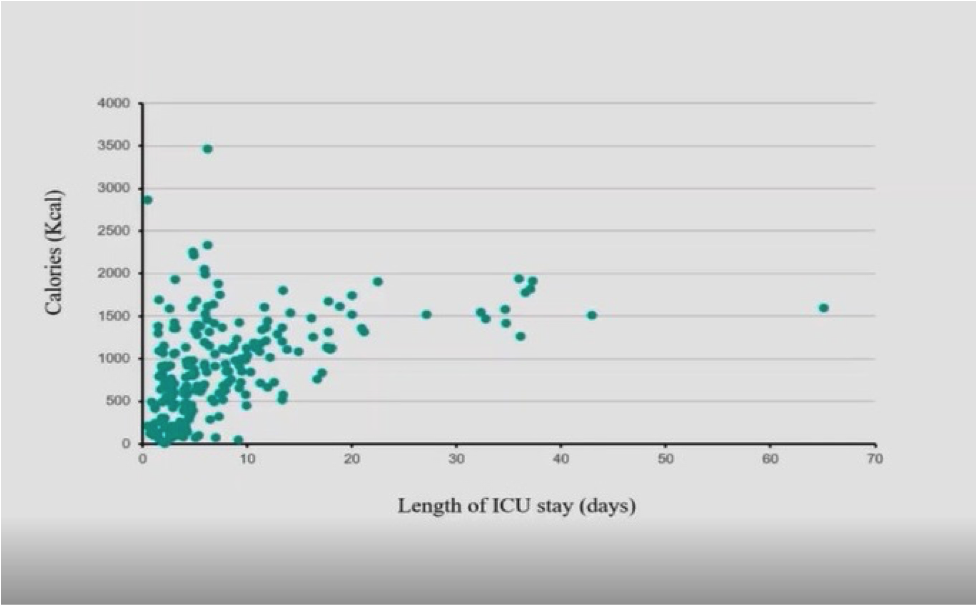

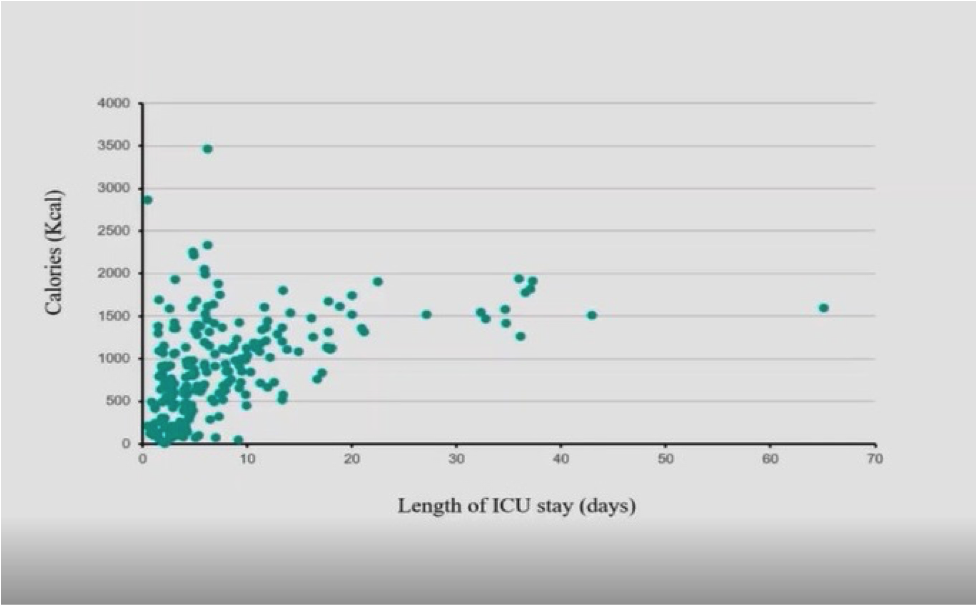

Figure 1 depicts the daily administered calories per patient. As is clearly evident, there is no consistency. During the first 10 days, administered calories range from zero to 2500 or 3000 calories. Calories level off and go up 1500 calories after 10 days. This is clear evidence that nutrition is not being monitored adequately.

Figure 1:

Figure 1: Daily administered nutritional calories per patient

Several reasons were considered to explain this inconsistency in daily nutritional delivery to patients, including:

• Nutritional calories vs. patient weight

• Nutritional calories vs. age

• Nutritional calories vs. daily fluid balance

• Nutritional calories vs. daily stool events

• Nutritional calories vs. number of transports out of ICU

• Nutritional calories vs. number of RASS+2 assessments/d

• Patients with catecholamine infusion

However, none of these explained the high heterogeneity of the amount of administered calories.

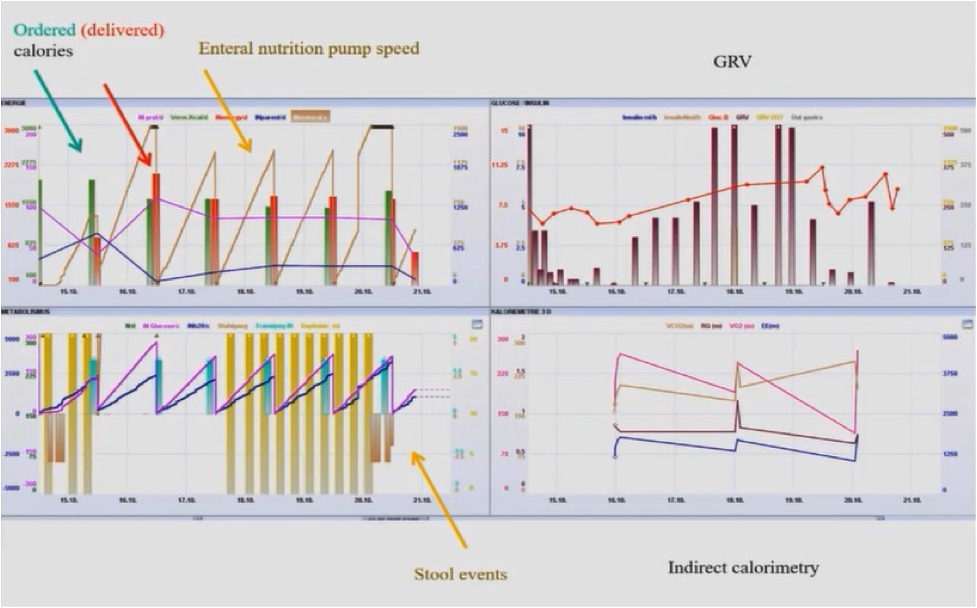

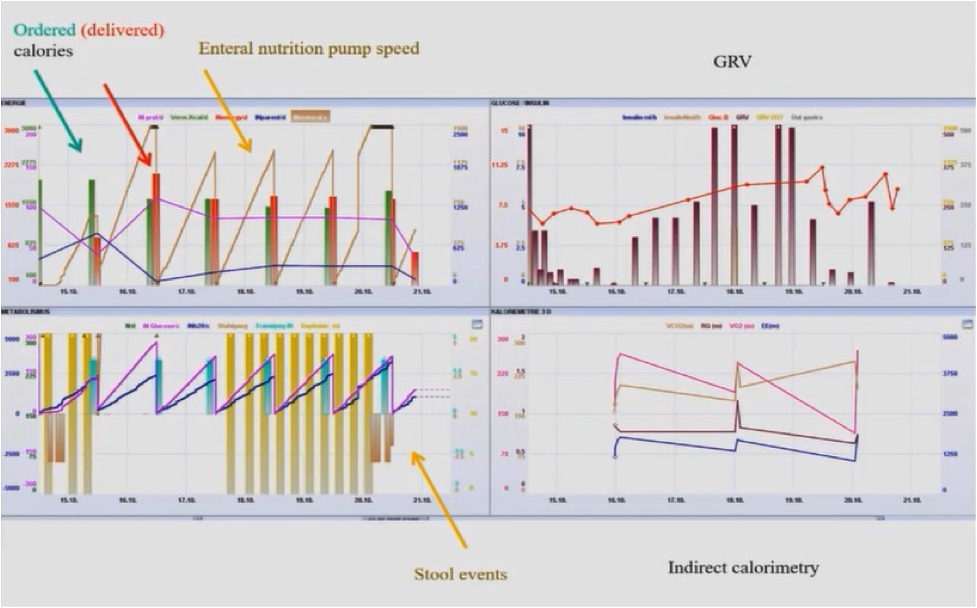

Figure 2 demonstrates another example of deviation between the nutrition that the patient should receive versus the nutrition that they actually receive.

Figure 2: Nutrition Delivery to the Patient

The above figure clearly shows that during the first three days, this patient didn’t get an order for calories for nutrition and didn’t get any nutrition. In the next three days, they got some nutrition but there was no order. This was probably because the nurses started the nutrition protocol as they never received an order to do so. On day four, the doctor made the order, but the order that is delivered the next day is only half as is demonstrated by the decrease in the red column. Nothing is delivered the next day. Similarly, if we evaluate the gastric residual volume (GRV), we see that it is at 260 although our protocol says we can go up to 500 GRV. The first three days are okay as demonstrated here but then there are no orders. It is thus evident that there is no consistency in nutritional delivery. Sometimes there is an order but little delivered; sometimes, more orders are placed, and nothing is delivered; sometimes orders are placed, but half is delivered. There is no explanation for this discrepancy.

These examples indicate the need to improve how we monitor nutrition. It is important to monitor what is ordered and what is delivered, including meals. Nutrition should be monitored per kg of weight per patient and by determining how many calories the patient needs, and how much protein the patient needs. Any gaps should be documented so that clinicians know that there is a gap and they can then address it. It is also important to measure non- nutritional calories such as those obtained through citrate renal replacement therapy, dextrose infusion, or propofol1 in order to avoid the risk of overfeeding. If nutritional calories are adapted, too little protein may be delivered. This can be an important issue in certain patients such as those who need prolonged sedation, or those with traumatic brain injury etc.

Delivery of the right amount of protein is very important. In a retrospective study by Arthur van Zanten and his group2, they looked at patients who received less than 0.8g/kg/day and those who received more. The results showed that patients who received less than 0.8g/kg/day had the highest mortality. Patients who showed the best result were those who received less protein in the beginning, but then after three days, they received more protein, which seems like a good strategy.

Overall, it is evident that nutrition monitoring is as important as haemodynamic monitoring so as to determine any variability between recommended and delivered calories and proteins, and if such variability exists, the reasons for these differences should be documented, and concrete steps should be taken to correct the situation. Also, a large part of nutrition management in the ICU is left to the nurses, and while they do a good job, it is important that they receive support from the doctors so as to deliver adequate nutrition and follow protocols.

Figure 1: Daily administered nutritional calories per patient

Figure 1: Daily administered nutritional calories per patient

Figure 1: Daily administered nutritional calories per patient

Figure 1: Daily administered nutritional calories per patient